New Sanctions Regime Expands Frontiers of Financial Crime

The wave of sanctions following the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a punctuation point in the fight against financial crime. Meanwhile, the massive expansion in sanctions has coincided with a burst of activity on the part of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24 well over 1,000 individuals have been hit with financial sanctions that had the effect of freezing or confiscating assets held in various jurisdictions around the world. This has resulted in a greatly increased scope of activities for anti-financial crime compliance professionals – but at the same time it has, for many of those individuals, introduced a welcome element of clarity into everyday operations.

Money laundering – a subset of financial crime

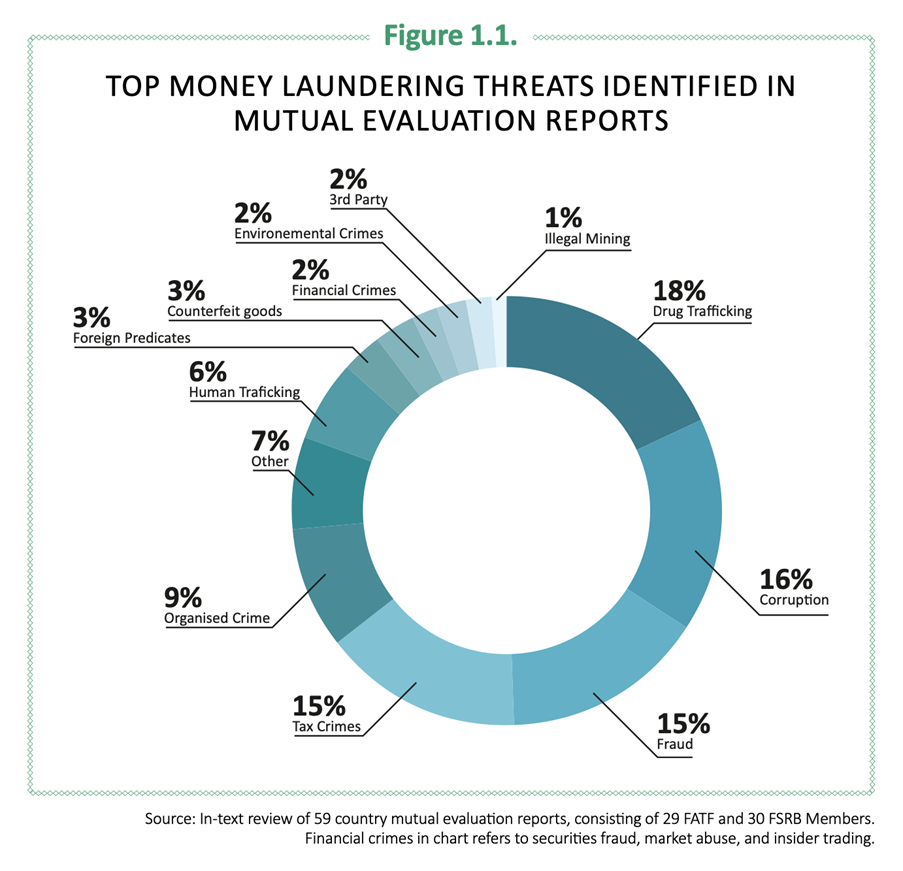

It is often mistakenly believed that the overwhelming preoccupation of bank financial crime compliance staff is with anti-money laundering (AML). In fact, AML is just a subset of the far wider realm of financial crime – the latter encompassing not just money laundering but sanctions evasion, bribery and corruption, drugs trafficking, human trafficking, counterfeiting, tax evasion, and modern slavery.

In the case of the recent expansion of the sanctions regime, money laundering has again moved center stage. Money laundering is the process of disguising the proceeds of a criminal act. But while money laundering volume has increased dramatically, this needs to be viewed in the context (and as a function of) the original crime, which is sanctions evasion. In short, it is necessary to decouple money laundering from financial crime, specifically sanctions evasion.

Sanctions expansion and ‘designated funds’

The circumstances that led to the expanded sanctions regime has prompted a large degree of soul-searching in Western jurisdictions that have for years effectively provided sanctuary for assets that heretofore were considered legitimate but, since the expansion of the sanctions regime, are ‘designated funds’ and must first be identified and reported to the relevant sanctions authority, and cannot be processed without explicit approval from that authority.

And this expanded sanctions regime has coincided with an active period for the FATF. The FATF is an inter-governmental body that sets international standards in these areas with a brief “to generate the necessary political will to bring about national legislative and regulatory reforms.” Central to this are the FATF’s 40 Recommendations issued in 2012.

FATF cites “substantial challenges”

April saw the FATF publish a ‘landmark’ report on the state of effectiveness and compliance with FATF standards as part of a three-year strategic review of its operations. FATF reports that 76% of countries have now satisfactorily implemented its 40 Recommendations in their laws and regulations – a “significant improvement in technical compliance, which stood at just 36% in 2012.”

Yet many jurisdictions, according to FATF, still face substantial challenges in taking effective action commensurate to the risks they face. “This includes difficulties in investigating and prosecuting high-profile cross-border cases and preventing anonymous shell companies and trusts being used for illicit purposes.”

It is this issue of beneficial ownership that has risen to the top of the agenda in the fight against financial crime. By coincidence, the FATF in early-March adopted amendments to Recommendation 24 and its Interpretive Note, which “require countries to prevent the misuse of legal persons for money laundering or terrorist financing and to ensure that there is adequate, accurate, and up-to-date information on the beneficial ownership and control of legal persons.”

For Lee Byrne of the Great Chatwell Academy of Learning, a global financial crime specialist who advises and trains a range of international financial and non-financial institutions, including AML supervisors, the expanded sanctions regime has brought increased work but has in many respects made the job of financial crime compliance professionals somewhat easier.

Financial crime compliance and commercial tension

“We now have a definitive statement of who the bad guys are,” says Byrne. “Until now people had a personal view of these people of who maybe they didn’t approve of but they weren’t definitively labeled as criminals. Now that they’ve been sanctioned and their assets designated and are subject to licensing constraints, some people are welcoming that.”

According to Byrne there will always be a tension between financial crime compliance professionals and the commercial side of the business. For the latter, it is understandable that clients and prospects are considered innocent until proven guilty, because the vast amount of customers are honest people. The new sanctions regime now makes it easier to delineate between those two groups.

“The commercial team are important to support the growth of businesses and can be as much as 60-80% of the business resource and then there’s a smaller team of financial crime professionals. Until the last few years, some businesses were more supportive on the compliance side than others, others operated on a ‘just in time’ basis, and others considered failure as not material reputationally and a cost of doing business. We are now seeing more support for financial crime compliance, and thankfully, the attitude that ‘compliance is a business blocker’ is changing because of the hard work and dedication of compliance professionals in improving the effectiveness of training and communication, and explaining why compliance is important to stop crimes and terrorism, and not just to meet regulatory requirements.”

That doesn’t mean the job of compliance is anything other than a difficult one. The reality is that the assets of those newly fallen into the sanctions net left their home country long ago and are now spread and secreted across the OECD countries, invariably using proxies to make tracing of beneficial ownership so much harder. In that respect, any moves by the FATF improve the transparency of beneficial ownership of companies, and therefore assets, is to be welcomed.

Financial crime compliance requires change of mindset

But criminals will always be one step ahead unless there is a change of mindset on the part of financial crime compliance professionals.

The reality is we publish outline principles of regulation three to four years ahead of actual implementation,” says Byrne, citing the historical FATF pronouncements in 2012 and the EU 4th Anti-Money Laundering Directive, published in 2015. This effectively gives criminals a roadmap and a head start to plan new and ever more sophisticated ways to avoid detection.

The answer, according to Byrne, is that compliance staff need to rely less on regulatory guidance and to take the initiative and encourage staff to develop a mindset that is “think like a criminal, otherwise you won’t make a meaningful impact.”

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials relevant to the content of this article:

- Sanctions

- Global Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- UK Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- US Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- Singapore Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- Hong Kong Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- Japan Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- UAE Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- Ireland Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- Kingdom of Bahrain Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- Ghana Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

- UK Anti-Bribery & Corruption (ABC)

- Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA)

- Ireland Anti-Bribery & Corruption (ABC)

- Anti-Bribery & Corruption (ABC) in Asia