Know-How spotlight: The replacement of LIBOR

Our latest quarterly Know-How update includes revised coverage of Interest Rate Benchmarks, including the key features of the new benchmarks, especially SOFR, that replaced LIBOR, and a detailed look at different SOFR-based products in the market.

The below content is taken directly from our Know-How tutorial, ‘Interest Rate Benchmarks – An Introduction’.

What are Interest Rate Benchmarks?

Interest rate benchmark (indices) are a form of benchmark that a lender may use as an element of the interest rate it charges a borrower for a loan. Benchmarks such as SOFR are not actual interest rates. Instead, the purpose of an interest rate benchmark is to show a number which reflects the “going rate” for a specified term and credit quality so that the index can be used for:

- The calculation of fair payments on products such as swaps or bank loans

- The compilation of discounting curves which are used in the context of “mark-to-market” discounting calculations

Interest rate benchmarks are central to the economic outcomes from a wide range of products such as:

- Loans

- Floating rate notes (FRNs)

- Interest rate derivatives (such as interest rate swaps and futures)

The interest rate index levels observed and used in these contexts have a direct and valuable impact on the economic outcomes experienced by the parties to contracts of these types. All parties should be confident that the index levels used are fair and reflective of market reality.

For a long time, the best known interest rate index types was LIBOR, especially USD LIBOR (discussed later in the tutorial). A broad consensus developed that LIBOR needed to be replaced with new interest rate benchmarks, preferably with the following attributes:

- Visible and transparent methodology

- Reliably available in all market conditions

- Readily applicable to “term” products

Uses of interest rate benchmarks

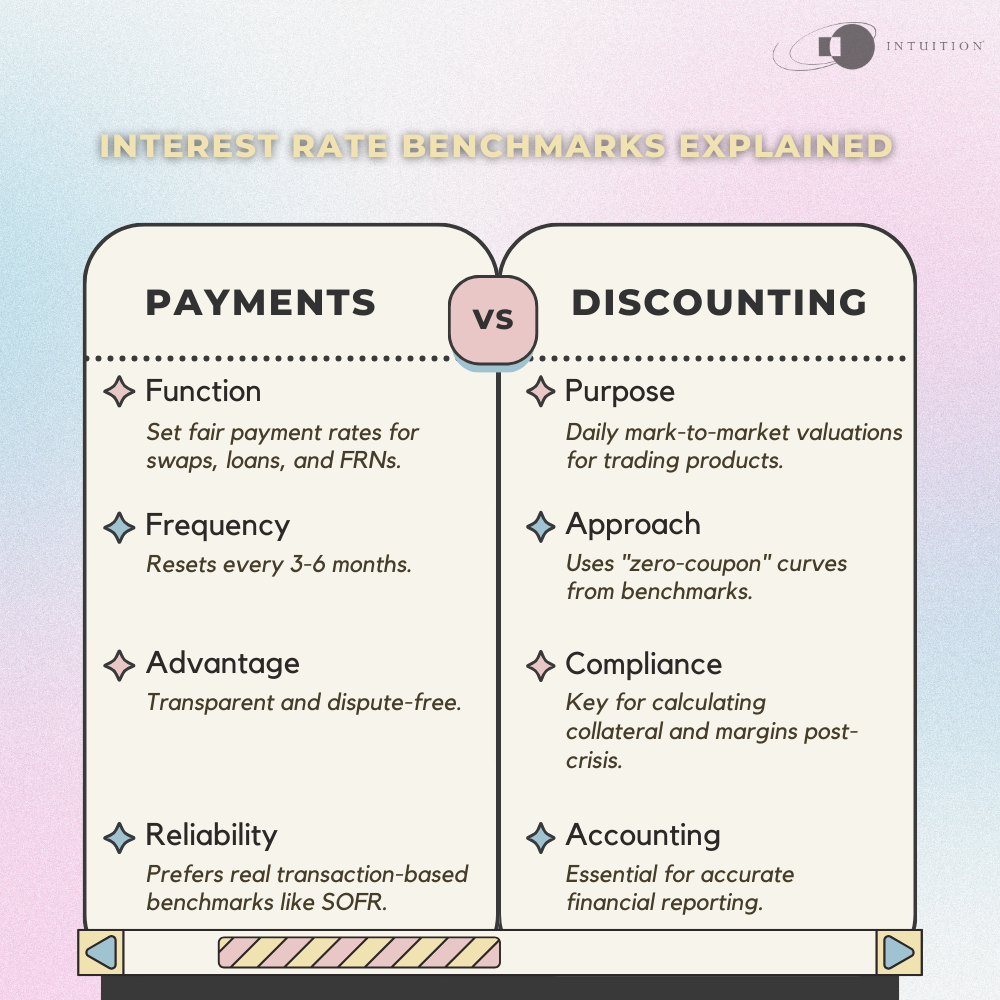

There are two practical uses of interest rate benchmarks.

Payments

Bank loans, FRNs, and the floating legs of interest rate swaps typically have payments that reset every three or six months. The processes of interest rate “reset” and of the compilation or sampling of the index used must enjoy the confidence of the parties making and receiving the resulting payments. Methodologies need to be sufficiently transparent so that the resulting value and payment amounts are beyond dispute.

Evidence of the index being in any way “faulty,” non-representative, or manipulated would very likely result in substantial legal uncertainty and potential litigation. An “opinion-based” benchmark (such as LIBOR) is certain to be more problematic in this regard than one based on real market transactions (such as SOFR).

Discounting

Products such as interest rate swaps, FRNs, and many bank loans are traded products. As such, product users will require mark-to-market information at least daily.

The calculation of mark-to-market values – especially in the absence of up-to-date and product-specific market prices – requires the compilation of discounting curves. Such curves, often known as “zero-coupon” curves, reflect the term structure and credit quality of the underlying indices. This was commonplace with LIBOR rates, and the same methodologies are now being applied in the context of SOFR, €STR, and other benchmark indices.

The calculation of mark-to-market values is central to a number of routines that are mandated by post-GFC legislation and regulation. These include the calculation of collateral requirements, as well as initial and variation margins for both cleared and noncleared products. Modern accounting also requires mark-to-market values for the purposes of profit and loss (P&L) calculations, as well as for updated balance sheet information.

Beginning of the end for LIBOR

The beginning of the end for LIBOR as an interest rate benchmark is widely considered to have been activated by the July 2017 comments from Andrew Bailey, the then Chief Executive of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the United Kingdom.

He observed that in spite of a number of reforms to the benchmark since the 2008 financial crisis, the underlying market for unsecured wholesale term lending to banks was “no longer sufficiently active” and was “potentially unsustainable (and) also undesirable, for market participants to rely indefinitely on reference rates that do not have actual underlying markets to support them.”

According to estimates published prior to LIBOR cessation, around USD 350 trillion in financial contracts were tied to LIBOR. Because the US dollar is the most widely used of the world’s currencies, US dollar LIBOR rates were the most widely used and cited.

The observation that the interest economics of as much as USD 350 trillion in financial products were being driven by a market where the volume of transactions was often minimal or non-existent gave rise to concerns of potential “moral hazard.” Some of these concerns arose from a number of scandals where interested parties submitted distorted information in order to further the economic interests of their own “books.”

Even prior to the GFC, some analysts and commentators had voiced concerns that the method for setting LIBOR rates was potentially flawed by distortions, especially given the reliance on the idea of an active and continuous market, despite evidence that banks tended to stop lending to each other at times of market stress.

Interbank deposit transaction activity has seen a near complete migration to overnight, this being the lowest risk part of the interbank universe. It should be noted here that the GFC happened at a time when the newly innovated OIS swap transactions were becoming mainstream. For example, a three-month OIS transaction allows the parties to the OIS to exchange three-month interest rate risk but with very little counterparty credit risk exposure potential. This allows banks to focus their interbank credit risk activity at the level of overnight while expressing term interest rate views through the use of OIS (swap) transactions with minimal credit risk.