From Crisis To Opportunity: Central Banks Seize The COVID-19 Moment To Embrace Change

Central banks worldwide are embracing extraordinary policies in a bid to stave off the worst economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The US Federal Reserve has announced a dramatic shift in its monetary policy approach, for example, and the European Central Bank has taken the unprecedented step of allowing for deviations from the capital key in its bond purchases. These and other developments suggest that the pandemic may lead to lasting changes in how the world approaches economic management and monetary policy.

2020 has been a year of extraordinary change. Millions of employees rapidly shifted to working from home, businesses retooled their product lines and processes virtually overnight, and teachers and students switched to online learning as education systems shuttered.

The upheaval caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has reached even the most conservative institutions, including central banks. The US Federal Reserve (Fed), for example, in August announced the most sweeping changes to its monetary policy approach in decades.

The Fed recalibrates

The Fed conducts its monetary policy under a twin mandate to promote both maximum employment and price stability. In the past, the central bank has interpreted this mandate to mean that it should keep inflation at or below 2% and that it should act – usually by raising interest rates – when unemployment falls to a level the Fed deems likely to promote higher inflation.

While this broad approach worked well in the decades following the 1970s when the Fed was grappling with inflation, it has been less appropriate in recent years and, indeed, has led to undesirable outcomes.

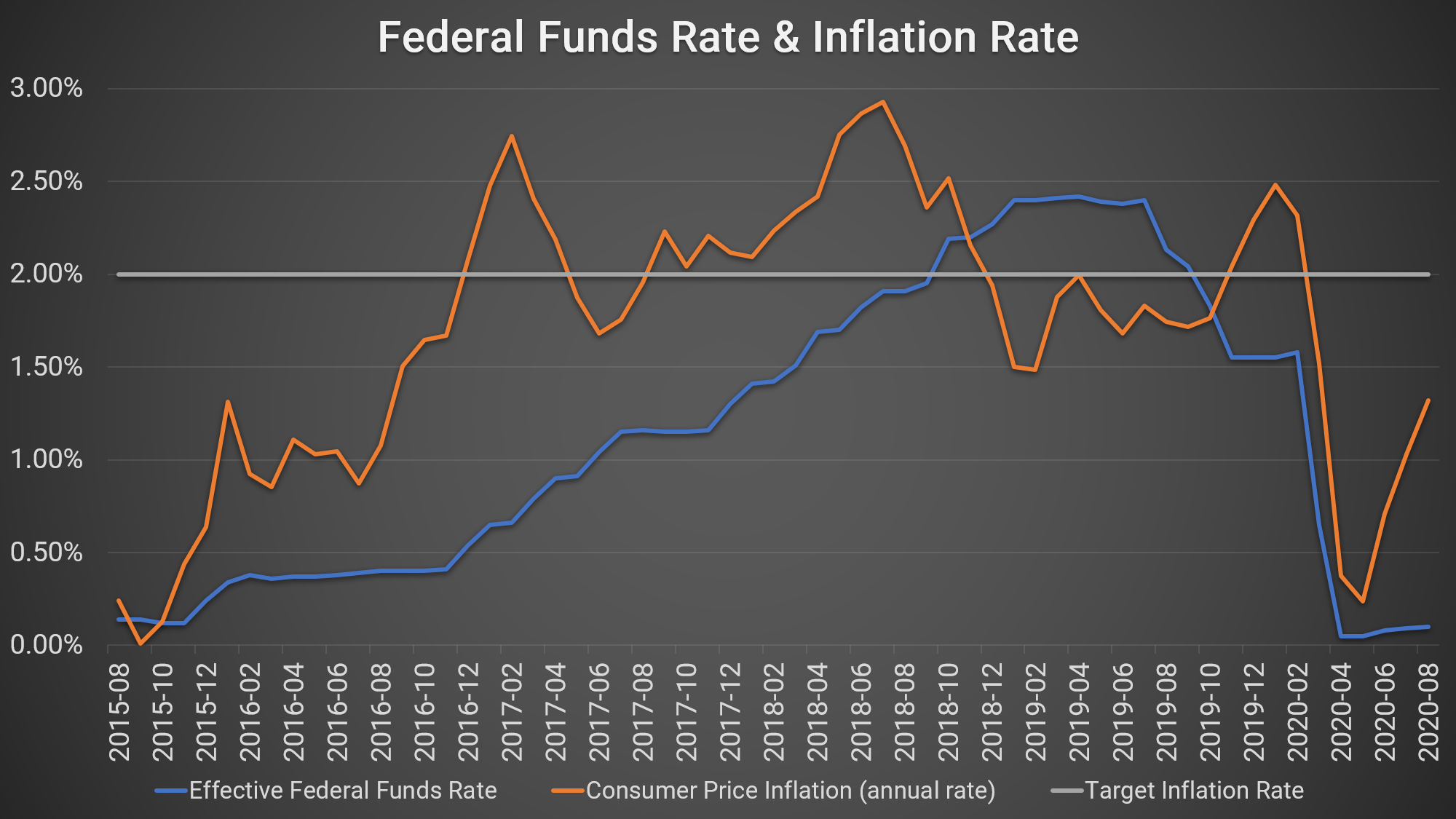

As the chart below illustrates, the Fed began raising interest rates in late 2015, even though inflation remained well below target. It continued raising rates throughout late 2018 and early 2019, even as inflation again fell below target. Some argued that the Fed’s decision to steadily raise rates led to slower economic growth and lower wage growth.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, September 2020.

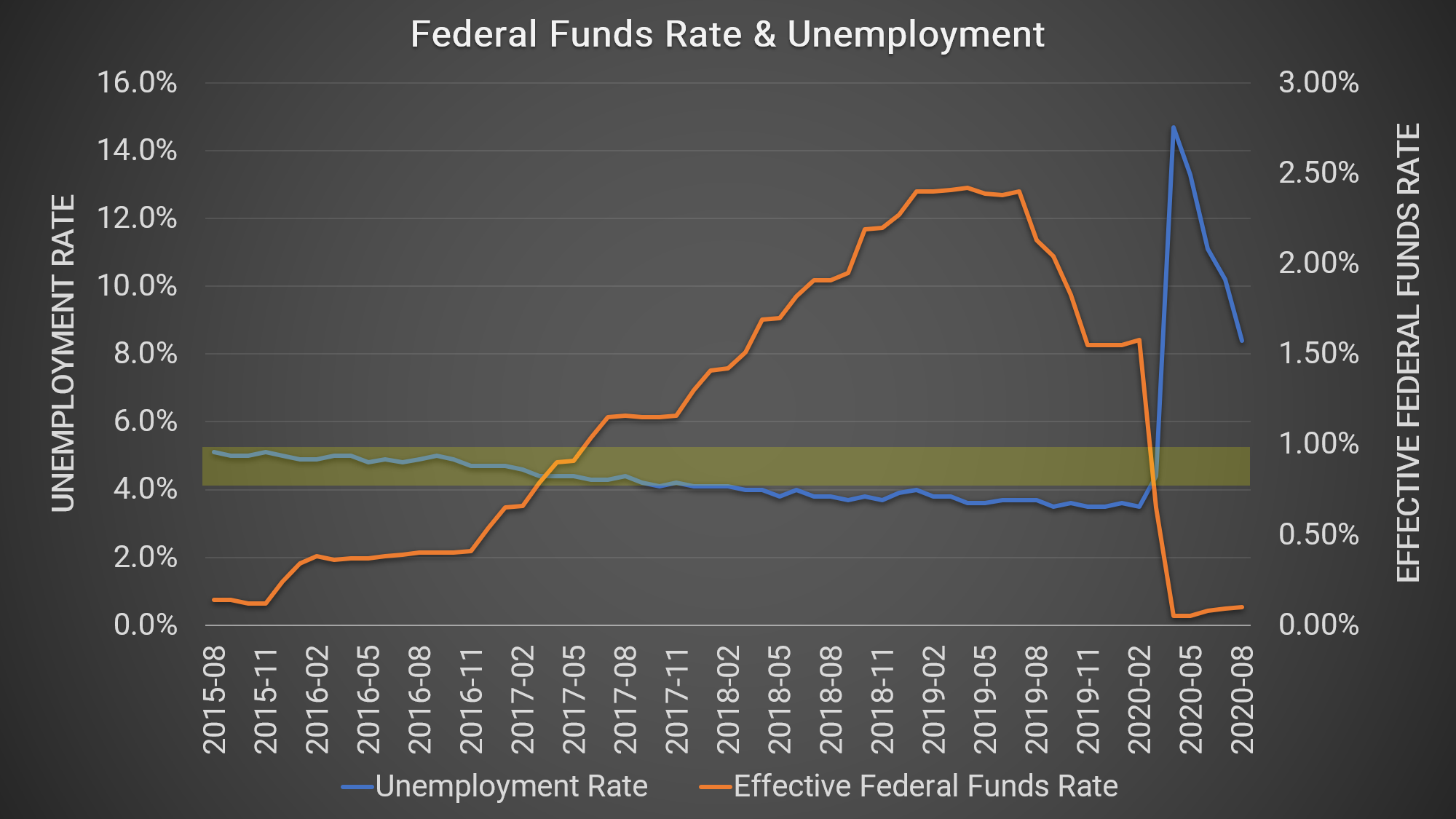

Certainly, looking only at inflation, the Fed’s approach seems to have been out of keeping with its mandate. However, when one also considers the unemployment rate (see chart below), the Fed’s hawkish stance becomes more intelligible. The Fed has generally considered an unemployment rate of between 5% and 6% to be the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) – the level of unemployment that does not lead to inflation.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, September 2020.

As US unemployment levels fell below the NAIRU range in late 2018, the Fed began to worry about the potential inflationary effects of ultra-low unemployment and to raise interest rates, even though inflation remained broadly contained. As unemployment continued to fall, the Fed continued to raise interest rates to avert inflation that never materialized.

Following a long-planned policy review that began in 2019 and concluded in July 2020, the Fed announced a set of strategic updates intended to avoid the monetary policy mistakes of recent years. Specifically, Fed chair Jerome Powell announced two major changes:

- The Fed’s 2% inflation target will henceforth be an average – periods of below-average inflation can be followed by periods of above-average inflation without triggering an interest rate increase.

- The Fed will no longer attempt to prevent employment from rising above its estimate of the maximum sustainable level (in other words, it won’t try to keep unemployment within the NAIRU range).

While these changes may seem relatively modest, by central banking standards they are consequential. The inflation-targeting change implies that the Fed will actively seek periods of above-average inflation after periods of below-average inflation in order to achieve an average rate of 2%, and the decision to no longer raise rates preemptively when unemployment falls below a certain level is a significant departure from the policy of the last five years.

Changes afoot elsewhere

The Fed is not the only central bank engaging in extraordinary monetary policies.

In the European Union (EU), for example, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it would deploy funds under its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) in a “flexible manner.” While this does not sound revolutionary, in the language of the EU’s central banking it was an important departure from

standard practice – usually, the ECB’s bond-buying programs are scaled in proportion to the capital key, which reflects each EU country’s population and contribution to euro area GDP.

By unhitching the PEPP from the capital key, the ECB gave itself the flexibility to provide support where needed, even if that meant a greater amount of smaller countries’ bonds would be purchased. This move was widely regarded as a step in the direction of a more comprehensive capital markets union among euro area economies, something that many politicians and policymakers have advocated for a number of years.

More broadly, central banks around the world have enthusiastically embraced monetary policy stances in the wake of the crisis that would have seemed impossible even 15 years ago.

The ECB, the Fed, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) – and, to a lesser extent, the Bank of England – have embraced direct asset purchases and virtually unlimited bond-buying programs, as well as a range of extraordinary measures related to bank capital, lines of credit, and previously unimaginable negative interest rates.

A brave new world of central banking

As monetary policy innovation continues apace and central banks enter new asset markets – in the US, for example, the Fed rolled out a program to lend directly to small businesses – many worry about the long-term inflationary impact of today’s policy choices.

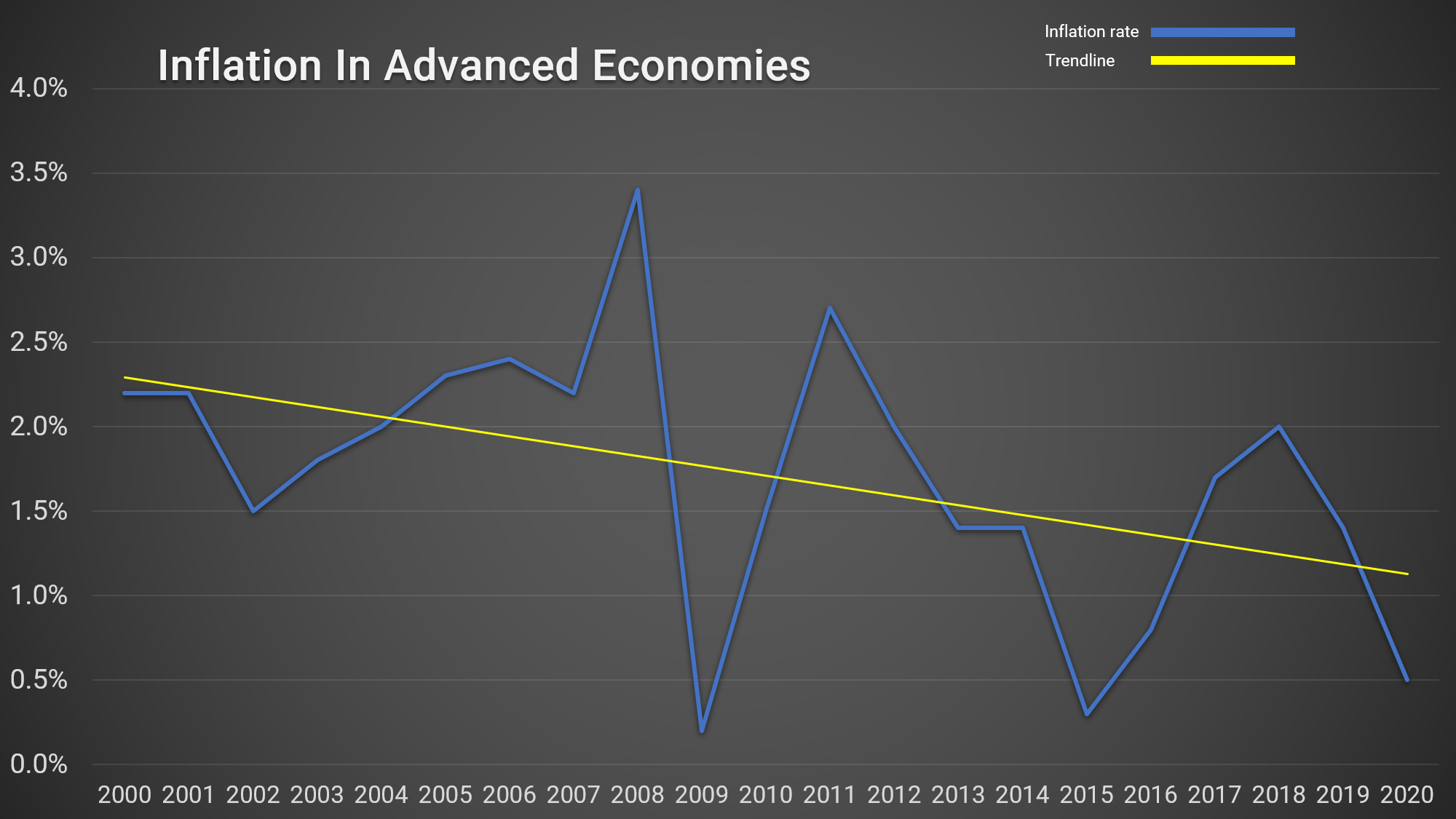

Yet, after two decades of steadily falling inflation in advanced economies – despite historically low interest rates – many observers believe that such policy innovation is necessary and appropriate to restore wealthy economies to robust health.

Source: International Monetary Fund, September 2020.

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials that are relevant to monetary policy and central banks:

- Financial Authorities (US) – Federal Reserve

- Financial Authorities (UK) – Bank of England

- Financial Authorities (Europe) – ECB

- Financial Authorities (Japan)

- Financial Authorities (China)

- Monetary Policy

- Inflation – An Introduction

- Inflation Indicators

- Employment & Unemployment – An Introduction

- Labor Market Indicators