Five Learning Design Practices

Designing learning is about creating an enticing, enduring and worthwhile learning journey for the individual and their organization. By placing the learner at the center and having a solid framework of thinking around your learning approach you’re on the way to creating a successful training story.

While we don’t adhere to a lockstep design approach all of the time – we always react to and provide an experience for the individuals and organizations at the center of our endeavors – we nonetheless use workable, pragmatic practices that leverage powerful design practice. Here we describe five learning practices that we believe deliver successful learning experiences.

***

This is the third article in a four part series which briefly describes how we go about the design of our learning. It gives an insight into some of the principles and practices that inform what we do. You can access the other 3 articles below:

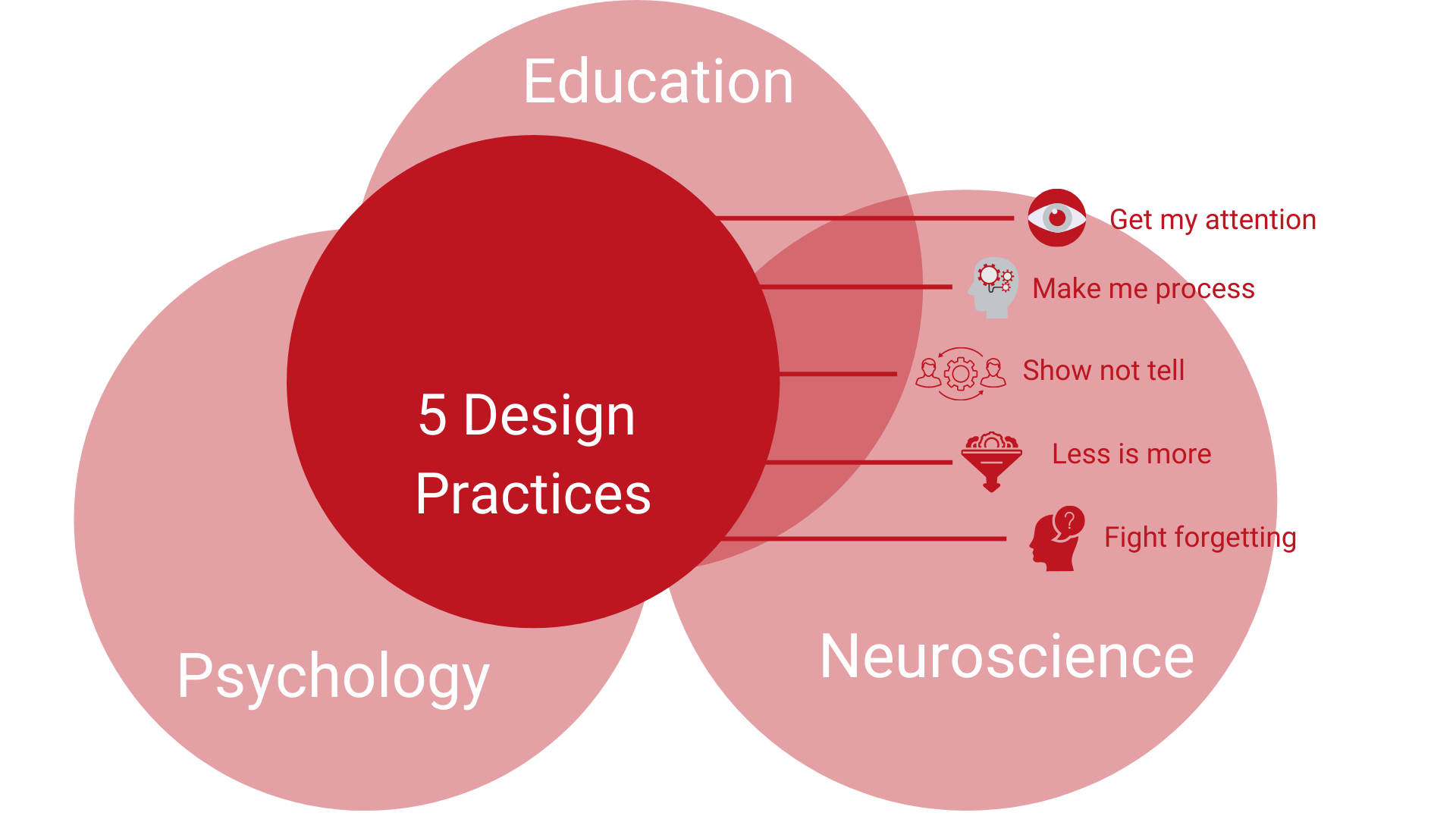

Principle 3 – Use A Consistent Set Of Design Practices

We know that all employees, no matter age or generational cohort, are faced with similar challenges to stay upskilled in a rapidly evolving workplace. They require and prefer learning that’s on demand, instant, happens in short bursts or “snackable” bites of content, occurs within the flow of work, is personalized to their needs and is authoritatively designed, developed and delivered when and where they need it.

While every learning design system is delivered in a highly intuitive and structured interface, what principles and practices make learning impactful? While designing and developing successful learning programs demands a complex mix of skills and processes, in simple terms, five practices underpin our design approach, whatever the delivery medium or blend. Coupled with extensive experience of working with business leaders in the modern workplace, we see these five practices as key to successful learning design.

These five practices maximize learning, optimize it so that our learners pay a great deal of attention to what we’re presenting, and help them take it on board, encode it deeply so that they are primed NOT to forget it.

They are:

- Get my attention

- Make me process

- Show don’t tell

- Less is more

- Fight forgetting

1.Get my attention

A simple fact is that cognitive resources of focus, attention, and memory are finite, for all of us. We simply can’t ask our learners to rely on willpower and concentration to get them through learning programs. We must grab attention and hold it.

We acquire attention in different ways in learning.

We seek to:

- Tell stories

- Surprise

- Create heroes (you, the learner)

- Fashion a First-Person Puzzle to solve

We create a reason to pay attention to content. There’s a goal, a time pressure, a sense of urgency, we always react to the urgent, not necessarily the important, so we make our material and content urgent. Surprise can get a learner’s attention with an attention-grabbing title or copy and accompanying image.

Attention is not open-ended. Medina (2008) in Brain Rules cites the ten-minute rule. After ten minutes, attention declines. To remedy this problem, switch gear, introduce something new or fresh every ten minutes and design learning nuggets of about ten minutes in duration.

2. Make me process

Our approach to learning design centers around engaging the learner in an active learning process, where the learner is engaged, involved and taking an active (rather than a passive) role in the learning process.

Peter Doolittle, a leader in educational research on memory and learning, addresses the role that working memory capacity (WMC) plays in learning in multimedia environments.

WMC is the ability to control attention and remain focused on a task at hand while simultaneously retrieving relevant information from long-term memory. Doolittle raises the challenge of enhancing learning by making learners process what they’ve learned. He describes processing meaning immediately and repeatedly[1].

We make learners process in different ways in learning, both in ways that require them to interact directly with the learning (for example through inline questions and interactive animated sequences) as well as with a range of other techniques that call upon them to actively process.

We:

- Ask learners to reflect, consider, apply content to their own environment

- Repeat content and make it rich with meaning and examples

- Regularly prompt learners to check their understanding via inline questions and providing clarification of any misunderstanding

- Force people to consider, problem solve, make connections, to relate to their own context

- Ask learners to reflect on their own situations or experiences

- Use different language, media

- Bring in practice, get learners to practice a skill set

- Include short end-of-tutorial summaries that briefly summarize the prior learning and prompt them to recall

The more elaborately learners encode at the moment of learning, the stronger the memory.

3. Show don’t tell

We are about real-world applied context and situation. One of the biggest challenges in adult training and development is making sure that learners carry the training back to the job (learning transfer). To this end, we apply a Show Don’t Tell practice.

What do we mean by that? We mean that by producing training that is highly relevant to learner, that replicates as faithfully as possible, their real work environment offering the cues and prompts they encounter in their work place and by immersing them in real world scenarios and realistic activities, we have a better chance of learners developing proficiency and ultimately bringing their new skills and knowledge back to the job.

A key aspect in real-world mirroring, is allowing learners experience consequences (Show) rather than simply telling them (Tell). Let’s take an office worker who is exploring a learning scenario around compliance. In one choice-based interaction, he fails to follow a compliance protocol leading to an error that has organization-wide implications. Rather than telling him ‘Oh-oh you’ve just made a crucial mistake!’, we allow the learner experience the complaining emails arrive, be forced to reply to colleagues who ask for clarification and so on. In this way, we respect adult learners by recognizing that they know a lot and that they can deal with a lot. Clever, realistic scenarios and activities with real consequences help people practice and remember what they need to do on the job.

This principle, in conjunction with the ‘make me process’ principle, ensures that application in realistic contexts and the opportunity to practice skills are key elements of our design approach for modern adult learners.

4. Less is more

We realize WMC (working memory capacity) is limited, we seek to only give learners what they need, not extraneous overloading with gratuitous information. By understanding our audiences, and figuring out what learners really need to know, we trim our learning into light, easily accessible, relevant learning experiences.

Designing powerful learning is not about adding more; it’s about distilling down to focus in on what learners really need

5. Fight forgetting

The last of our core rules is about fighting forgetting or creating successful learning, and more productive learners.

A teacher loses learner attention typically after 10 minutes. A week after a course, you’ve forgotten 90% of what you’ve learned. In fact, a lot of what passes for common study habits and practice routines turns out to be counterproductive.

If we want to create more complex and durable learning, we must think about learning as a journey, rather than a once-off event. Intentionally planning learning across time and interventions, demands focus and commitment. Often organizations are happy with a ‘one and done’ approach. But be assured this does not typically lead to deep learning and is highly unlikely to transfer back to the workplace.

We think about learning as a many staged intervention journey, making use of a range of interventions across time ideally. We encourage self-testing, create difficulties in the practice, allow waiting until a little forgetting has set in, to restudy new material, and interleave one skill or topic with another to make learning more effortful and thus more likely to stick.

Part of fighting forgetting is in how we approach the process of teaching and learning.

We:

- Minimize information overload. (Remember less is more)

- Finish designing when there’s nothing left to take out

- Make our learning motivational, memorable and meaningful for the individual learner

- Build reflection points with strong challenging content, and encourage retrieval practice

- Encourage learners to actively engage with the content

- Space interventions with reminders

- Deliver assessments separate from learning to consolidate knowledge

- Consider learning as a journey, rather than a ‘one and done’ event.

If we want to deliver sustained performance over time for our individuals and organizations, we need to use a systematic, evidence-based approach to how we design our learning. Getting from learning to actual competence on the job, must be envisioned as a journey that requires a great deal of intentional design and support.

The evidence shows us that practices like targeting the attention of the learner, forcing active engagement rather than passive processing, mirroring real world complexity with realistic consequences while remembering all the time that the brain is designed to forget rather than remember will serve our craft well.

[1] TedTalk by Educational psychology research scientist, Peter Doolittle at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UWKvpFZJwcE