Does Rising Inflation Herald a new Economic Reality or are Higher Prices a Blip on the Radar?

After a long hiatus, inflation is back. In June, the US recorded its highest annual inflation rate since 2008 and in the EU, last year’s deflation has turned into a healthy level of inflation. The turnaround has taken markets and some central bankers by surprise. Bond prices, repo markets, and stock markets have been jittery in recent months as inflationary and interest rate expectations have fluctuated, and market participants are combing through regulators’ comments for hints on the medium-term outlook. The burning questions of the moment are: Is inflation back for good, and what does it all mean for markets and the economy?

For almost a decade, the inflation outlook has – for the most part, and in most places – been best summarized by a single word: muted.

In many parts of the world, particularly Europe, Japan, and to a lesser extent, the US, inflation has been consistently below central bank targets even as governments slashed interest rates and rolled out ambitious quantitative easing (QE) programs, sending sovereign debt-to-GDP ratios soaring. Even in traditionally inflationary emerging markets, both interest rates and inflation have been relatively subdued.

Inflationary Times

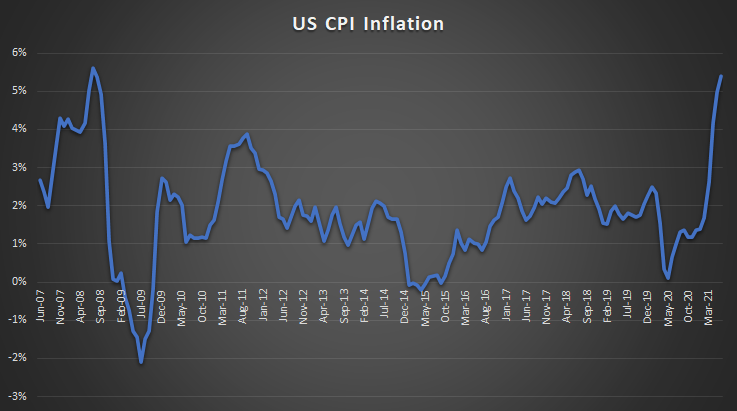

In the wake of the pandemic, the picture has shifted dramatically. In the US, for example, the consumer price index (CPI) rose 5.4% year-on-year in June, its highest level since August 2008.

The jump in inflation over the last few months has taken economists and policymakers – including US Federal Reserve officials – by surprise.

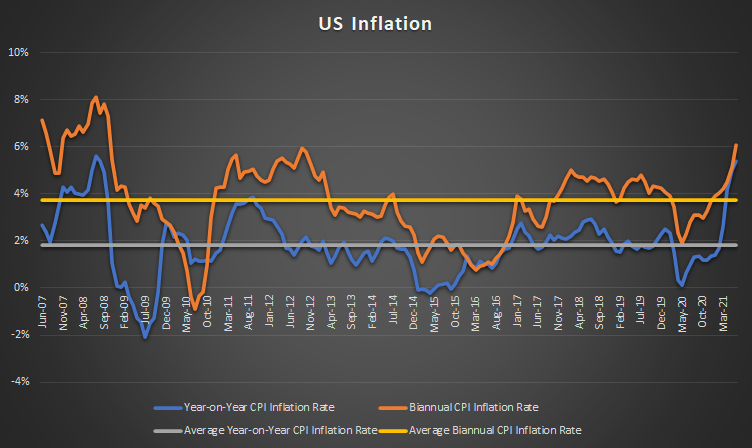

The Fed does not target the headline-grabbing CPI inflation rate, instead preferring the adjusted personal consumption expenditures index (PCE). Earlier this year, the Fed had predicted PCE inflation of between 1.4% and 1.7% for 2021, but between May 2020 and May 2021, PCE rose by 3.9%, far exceeding Fed expectations.

In response, the Fed initially appeared sanguine, signaling to markets that it would tolerate higher inflation as the US economy reopened. However, at its June meeting, the regulator struck a more hawkish tone, suggesting it would start raising rates by late 2023 – sooner than previously anticipated. As prices have continued to rise sharply, the Fed is coming under growing pressure to take a stronger stance against inflation.

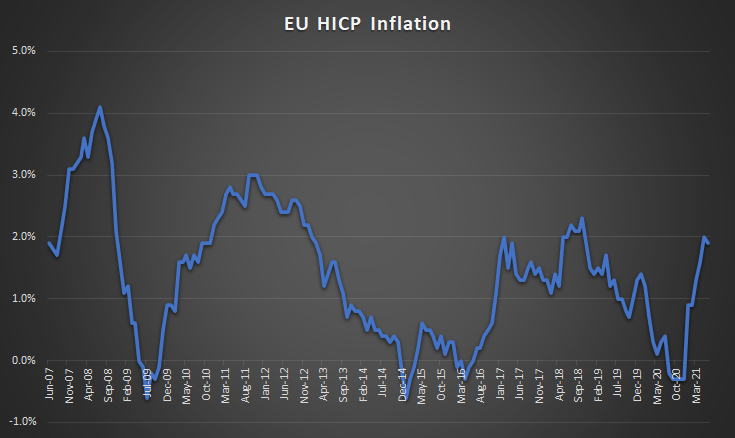

In the EU, inflation has shown a similar, but less dramatic rise, from a low of -0.3% in December 2020 to 1.9% in June 2021. Because European inflation has not exceeded the central bank’s targets, fears of early EU rate increases are muted.

Indeed, after an extensive policy review, the European Central Bank (ECB) recently revised its inflation target to 2% from a previous target of “below, but close to 2%,” with the added clarification that the new target is “symmetric,” meaning that both positive and negative deviations are undesirable, and that periods of above-target inflation would be tolerated if policymakers believe the increase is temporary. This change is widely seen as giving the ECB room to keep rates low as the European economy shakes off the impact of the pandemic.

Market Reaction

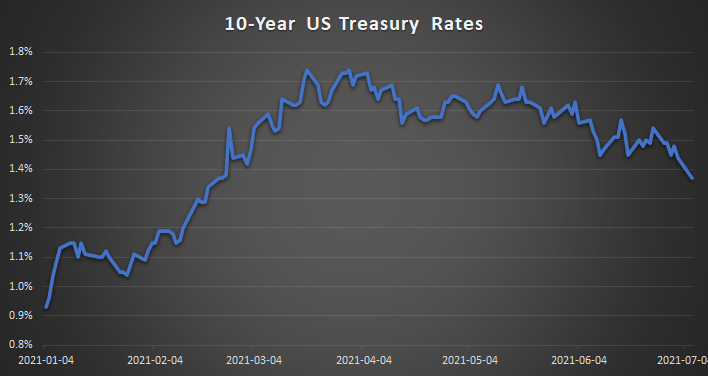

Markets have reacted tumultuously to the jump in inflation. As prices ticked up earlier in the year, for example, investors piled into the so-called reflation trade. On the assumption that US inflation and GDP growth would accelerate as America reopened and that the Fed would hold rates low to encourage growth and employment, many traders placed large bets against the price of ten-year US Treasuries. The idea was that long-dated debt prices would be squeezed by rising inflation.

However, after rising earlier in the year, yields on ten-year Treasuries have slipped lower thanks to the Fed’s more hawkish tone and a general sense that the buoyant economic environment – and associated rising prices – may not persist. Some prominent hedge funds were burned by the reversal in the reflation trade, including Caxton Associates and Rokos Capital.

Inflation Outlook

As the reflation trade crunch illustrates, there is significant market uncertainty about the outlook for inflation and interest rates, and market participants are placing bets in all directions.

For its part, the Fed maintains that the spike in US inflation is transitory.

For one thing, much of the inflation increase reflected in recent data can be attributed to a small handful of products and services. Just three components of the CPI basket of goods, namely used cars, auto insurance, and airfares, accounted for nearly half of the increase in inflation measured in June, for example.

The spikes in prices for these items are the result of several unique factors. Used car prices have risen because problems in computer chip supply chains are impacting the production of tech-heavy new cars. Airfares are rising from a very low base as travel resumes, and auto insurance premiums are normalizing after being slashed during the pandemic as miles driven fell. None of these factors is expected to endure into the next year or two.

Similarly, inflation in many regions has been driven, in large part, by a rise in energy prices. However, the rise comes off a very low base – oil prices fell below $30 a barrel last year as demand crashed, and many producers slashed production in response. Oil prices have since recovered to around $70 a barrel as demand has returned – observers expect that producers will raise production and that this will likely prevent prices from continuing to rise so steeply.

In other words, most economists believe that transient factors are driving price increases from a low base. Once supply chains normalize, people get back to work, and coronavirus-related limitations on production and travel ease, inflation should fall back to the target rate. There is some evidence to support this view. For example, while the US June numbers look dramatic on a year-on-year basis, when comparing prices across two years – looking at the rates of increase between June 2019 and 2021, June 2018 and 2020, and so on – the spike is far less pronounced. This suggests that in some ways, the rise in prices experienced this year represents “catch up” inflation, rather than the start of a new trend.

However, not everyone is convinced by these arguments. Noting that the Fed’s predictions have consistently underestimated inflation by a significant margin over the last year, some argue that the Fed is not taking the threat of inflation seriously enough. Should prices continue to dramatically overshoot Fed estimates, policymakers will face tough questions from business and political leaders.

Citing the large number of unfilled jobs in the US and rising wages, critics of the Fed’s stance argue that the ingredients of an inflationary environment are present. Others point to the rapid rise of house prices, which are not included in most central banks’ inflation calculations, as an indicator that economies are running hotter than policymakers realize – not only in the US but also in Europe and the UK.

Sensitive to this concern, the ECB has promised to incorporate the cost of owning a home into its inflation measure, the HICP (Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices). However, the ECB, like the Fed, believes that higher inflation is a temporary phenomenon driven by a set of special circumstances as economies reopen.

Indicators to watch

At this point, it is still unclear whether inflation is back for good, or just for now. However, some key indicators may offer insight into the longer-term outlook:

- Jobs and wages – As economies reopen, many employers are finding it hard to fill vacancies. In both Europe and the US, some businesses are blaming high unemployment benefits or furlough schemes, saying that these discourage workers from returning to their jobs. Others blame lingering fears of the virus and, in some places, low vaccination rates and uncertainty about restrictions. As governments unwind their worker protection programs, vaccination programs accelerate, and infection rates fall, it should be easier to find employees. Market players can watch vacancy rates and wage data to see if workers are heading back to their jobs – if so, higher inflation may indeed prove transitory.

- Consumer spending – As hospitality and travel have begun to reopen, consumers have been opening their wallets. Spending on meals out, entertainment, travel, car rentals, food, alcohol, and clothing has skyrocketed in most places. Some anticipate sustained demand as consumers spend down the savings they accumulated during the pandemic. Others, however, believe consumers will moderate their spending after an initial burst of enthusiasm and – scarred by the experiences of the last eighteen months – will continue to save as protection against future downturns. Market participants can look out for a slowdown in consumer spending, which may indicate that inflation will moderate.

The global economy is poised on a knife-edge. As the world slowly emerges from its pandemic downturn, progress has been swift in some places and slow in others. Supply chains, production lines, and workers have been disrupted and displaced, and rebuilding takes time. Inflation may fall as economies normalize and consumers revert to previous patterns. However, any lingering scars – a permanent shrinkage of the labor force, for example – may drive sustained inflation. Unfortunately, only time will tell.

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials that are relevant to inflation and central bank policies:

- Economic Indicators – An Introduction

- Inflation – An Introduction

- Inflation Indicators

- Monetary Policy Analysis

- Financial Authorities (US) – Federal Reserve

- Financial Authorities (Europe) – ECB

- Financial Authorities (UK) – Bank of England

- Bond Markets – An Introduction

- Bond Markets – Trading

- US Bond Market