Deposits in Danger as Banks Push Back

In the wake of the crisis, many people are holding on to a stockpile of cash while they wait to see if the global economy rebounds. However, around the world, bank customers are finding their institutions strangely reluctant to handle these deposits. From limits on deposit amounts to threats of negative interest rates, banks seem to be doing all they can to avoid taking on additional deposits. What accounts for this strange situation, and what does it mean for banking customers?

In regulatory circles, banks are often referred to as “deposit-taking institutions” – so central to their business models is the practice of providing a safe home for clients’ cash. In most jurisdictions, bank deposits enjoy a unique status; they are protected from loss, guaranteed by national insurance schemes, and given a high rank in banks’ capital stack. Indeed, in many ways, the modern financial system is built on a foundation of deposits.

Yet today, this central pillar of the banking system may be under threat. Around the world, banks are trying to squeeze deposits off their balance sheets, using a range of mechanisms to encourage – or, in some cases, force – clients to take their money elsewhere. Why have banks soured on deposits?

Too much of a good thing

Over the last year, cash on deposit at banks has skyrocketed. In the US alone, Federal Reserve data indicates that bank deposits rose by over $3 trillion between the end of the fourth quarter of 2019 and the end of the first quarter of 2021, while in Europe, bank deposits rose by more than 10% between July 2019 and July 2020.

Much of this is a consequence of the global pandemic. As economies locked down, businesses and consumers hoarded cash, either unwilling or unable to spend it. Government furlough schemes, loan programs, stimulus checks, and other pandemic-related financial supports further fattened up deposit accounts. The result is an unprecedented amount of cash on hand.

On the face of it, this should be a good thing for banks. Their core business is to accept deposits and then use that capital to provide loans, earning a profit on the difference between the interest rates they charge borrowers and the rates they pay depositors.

But the situation is not quite that simple. Banks are complex institutions and regulatory changes – particularly the provisions of Basel III – have meant that there really can be too much of a good thing.

Borrowing spree

One problem has to do with the “Liquidity Coverage Ratio” or LCR. Under the Basel Committee’s LCR rules, banks must keep a quantity of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) on hand to cover 30 days of projected cash outflows.

Essentially – and reasonably enough – banks are expected to hold enough liquid assets to cover their expected outgoings. They must calculate these expected outgoings applying various formulae to their liabilities.

From the bank’s perspective, deposits are a liability. When a household or corporate deposits money at a bank, that money is – in practical terms – a loan. The bank is expected to repay that money on demand, along with some agreed rate of interest.

When deposits grow rapidly, banks essentially engage in a spate of unplanned borrowing. Over the last year, for example, US banks have unintentionally borrowed over $2 trillion from US households as consumer deposits have risen.

To ensure they can repay these unplanned borrowings, banks must increase the amount of capital – especially low-yielding HQLA – they have on hand. This is a burden for banks and puts pressure on their balance sheet management.

In addition to the LCR, other prudential rules around leverage ratios place limits on how much banks can borrow – generally, they may only borrow up to certain limits associated with the amount of shareholders’ equity they have.

Sudden increases in deposits can push banks over their borrowing limits, which may force them to cut back on their activities, as well as reducing their return on equity. Recognizing this, regulators temporarily relaxed these limits during the pandemic to avoid a reduction in lending – but this easing is set to wind down in the year ahead, putting growing pressure on banks’ capital management.

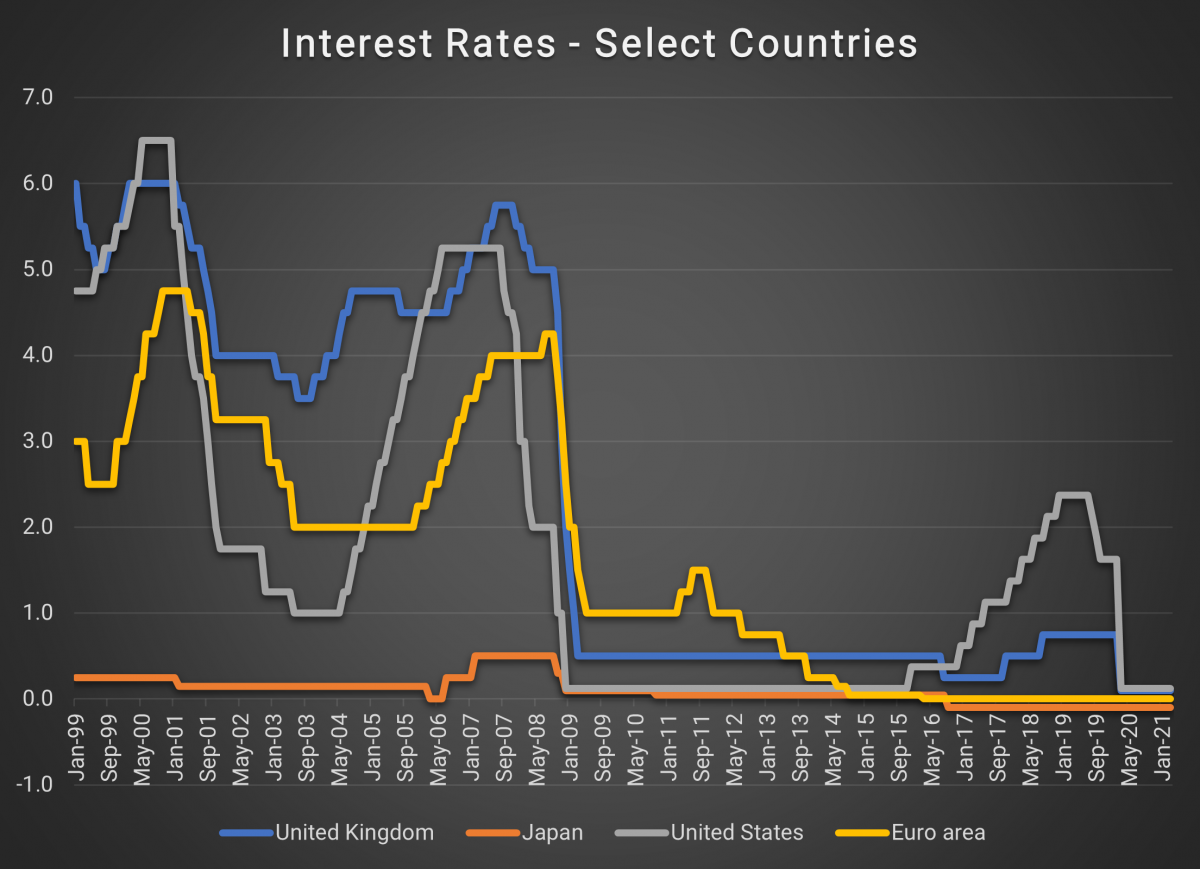

Another factor that may indirectly reduce banks’ appetite for deposits is persistently low interest rates. In some jurisdictions, interest rates are negative, and – in some cases – banks must pay for the money they hold on deposit at their central banks.

The goal of negative rates is to lower borrowing costs in the economy and fuel more lending by discouraging banks from holding reserves. However, low rates place significant pressure on banks’ profit margins, especially because they are generally reluctant to charge savers negative rates on their deposits even when they must pay negative rates themselves. Thus, low or negative rates may disincentivize deposit-taking.

Bank for International Settlements. Central Bank Policy Rates. May 2021.

Tough times for depositors

All of this adds up to a difficult environment for savers. To avoid the need to shore up their capital reserves and to avoid the complications associated with too much borrowing, banks are finding creative ways to discourage deposits. They are lowering already rock-bottom rates and imposing “deposit limits” – setting a cap on how much customers can keep in their accounts. On the corporate side, some banks are encouraging clients to move their cash into money market accounts or other deposit alternatives.

If consumers and businesses spend down their cash reserves as anticipated – many economists view last year’s excess deposits as “pent-up demand” that will come online as economies reopen – then banks may not need to take further action. But if deposits remain elevated, more extreme measures may be on the cards, including charging customers for cash on account – banks in Europe have already begun to warn customers with large deposits to prepare for negative interest rates.

As the financial system attempts to process the unprecedented fiscal and monetary support rolled out during the pandemic, we may be in for a brave new world of disappearing deposits.

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials that are relevant to banking and deposit-taking:

- Banking – Primer

- Business of Corporate Banking

- Business of Consumer (Retail) Banking

- Bank Balance Sheets

- ALM & Treasury Management – An Introduction

- Financial Regulation – An Introduction

- Basel III – An Introduction

- Basel III – Liquidity & Leverage

- Liquidity Risk – An Introduction

- Liquidity Risk – Measurement

- Liquidity Risk – Management