Combatting COVID-19: How Central Banks Are Responding To The Crisis

Global central banks – namely the US Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) – have responded with unprecedented intensity to the economic crisis that has followed in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. They have rapidly deployed a host of traditional and nontraditional monetary tools to help fight the global meltdown. Trillions of dollars, euro, and yen have been created to shore up the global financial system and to provide much-needed liquidity to households and businesses. However, their responses have been neither uniform nor fully coordinated, and many are asking whether they have done enough – or perhaps, too much.

The Fed, the ECB, and the BOJ have pulled out all the stops in their response to the Covid-19-induced global economic slowdown. They have maintained negative or rock-bottom interest rates and aggressively expanded quantitative easing (QE) programs into previously unchartered waters – including, to various degrees, announcing unlimited QE.

Their response indicates that central banks learned the lessons of the global financial crisis (GFC) when delayed action resulted in severe consequences and widespread criticism. During the present crisis, they have responded quickly, often well before official measures have clarified the scale and severity of the downturn.

This has garnered praise from many economists and financial market participants, who have lauded the early and massive interventions. However, central banks have also attracted criticism from those who worry that the dramatic increase in their balance sheets will lead to long-term inflation and, possibly, stagflation and economic depression.

The US Federal Reserve response

The Fed’s response to the coronavirus downturn has been unprecedented, even by the standard set during the GFC.

In its June minutes, the Fed provided a particularly gloomy analysis of the prospects for the US economy. It expects unemployment to remain elevated until the end of 2021 and foresees a 6.5% contraction in 2020 GDP, followed by a 5% expansion in 2021 – insufficient to return the economy to its 2019 size.

In line with this grim outlook, the Fed’s interventions have been broad and deep. It has cut its target federal funds rate by 1.5 percentage points since March, to a range of zero to 0.25%. It also provided clear forward guidance in June indicating that it will likely keep rates low until at least 2022.

More importantly, it has resumed its massive, GFC-era asset purchase programs, committing to purchasing “unlimited” quantities of Treasury securities, government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities, and commercial mortgage-backed securities. It has reestablished GFC-era programs such as its Primary Dealer Credit Facility, which provides low-interest funding to primary dealers, and its Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF), which acts as a backstop to money markets. It has also expanded its repurchase agreement (repo) operations, offering an essentially unlimited amount of money.

Additional measures include easing regulatory capital buffer rules, lowering the rates on the funding it provides banks through its discount window lending program and, notably, establishing new facilities to lend directly to corporations – the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF), will allow the Fed to directly purchase corporate bonds in the primary and secondary markets. The Fed also reinstated its GFC-era Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), allowing it to purchase commercial paper, and announced a controversial Main Street Lending Program intended to support lending to small businesses. It has also revealed a new Municipal Liquidity Facility that will allow it to lend to state and municipal governments.

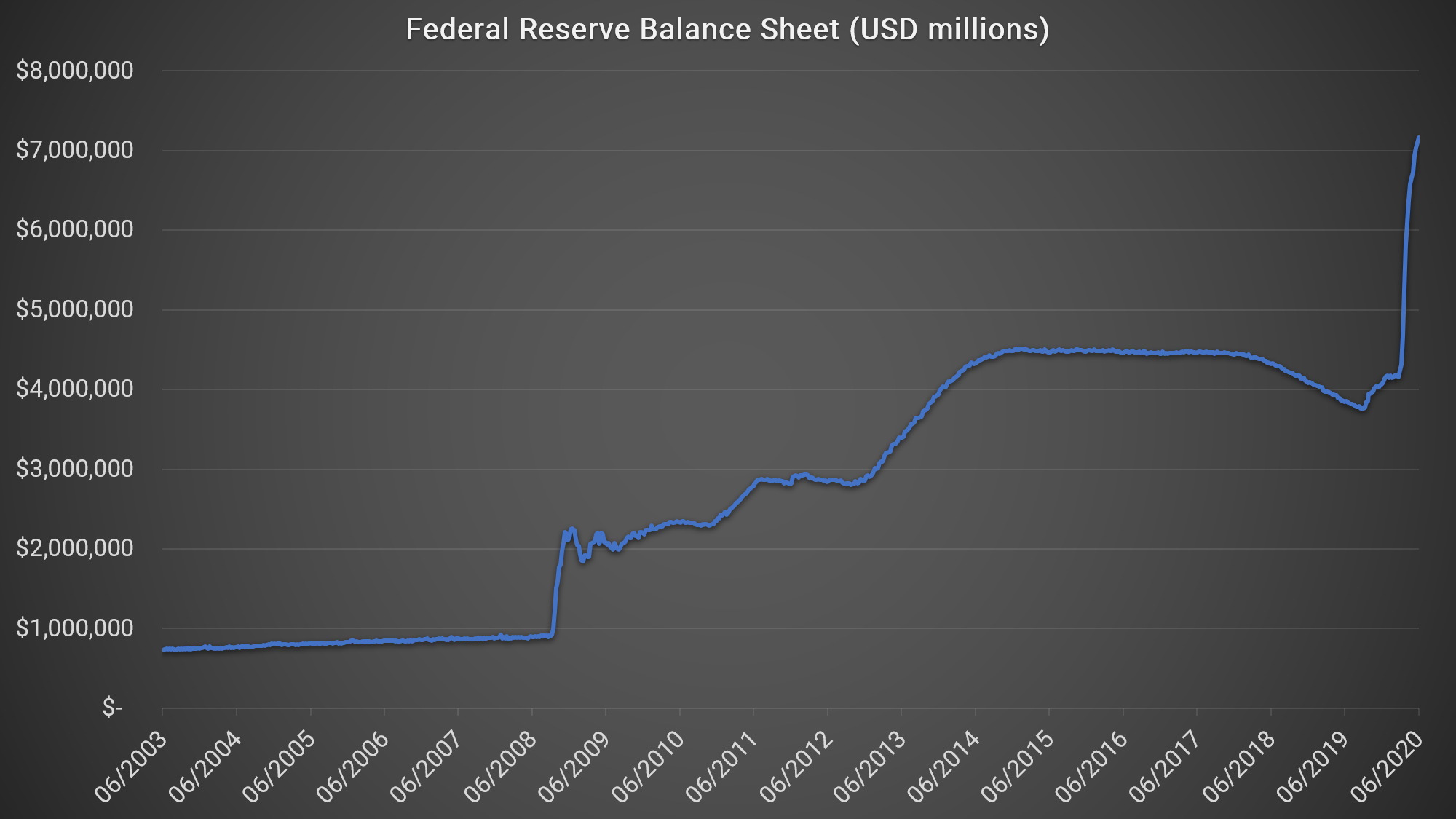

As a result of these measures, the Fed’s balance sheet surpassed $7 trillion in early June. This represents record growth; the Fed balance sheet grew by around $1.4 trillion in the two years following the 2008 downturn, but it grew by $2.9 trillion in the three months following the March stock market crash. Today, it stands at around 40% of US GDP, compared to just 6% in 2007.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. US Federal Reserve Assets. June 2020.

The European Central Bank response

The ECB, which sets monetary policy for the 19 European nations that use the euro, operates in a very different environment to the Fed. There is no central, eurozone-wide fiscal policy. Rather, each nation sets and administers its own fiscal response. There is also no central eurozone government bond instrument analogous to US Treasures – each national government issues its own bonds. This places unique constraints on the operations of the ECB. Nevertheless, it has responded strongly to the coronavirus crisis.

The ECB’s outlook for the economy is bleak – it foresees an 8.7% contraction in the eurozone in 2020, followed by a 5.2% expansion in 2021 and anticipates that millions will remain on national employment support schemes for at least the next year. In this context, it has unrolled aggressive policy measures.

The ECB is currently running a negative interest rate policy: its target interest rate is set below zero in a bid to encourage banks to lend. In practice, few banks pay the penalty rate on their central bank deposits, but the rate is a strong signal of the ECB’s dovish monetary policy. The central bank’s forward guidance indicates it intends to keep rates at this level until eurozone inflation recovers to close to its 2% target.

The ECB has an extensive asset purchasing program (APP), purchasing securities ranging from government bonds to regional and local authorities’ bonds, corporate bonds, asset-backed securities (ABS), and covered bonds. It was engaged in ongoing QE before the crisis hit in the first quarter. Since then, it has expanded its QE program and rolled out a €1.35 trillion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) to purchase additional securities.

Traditionally, the ECB’s bond purchases have been scaled in proportion to eurozone governments’ capital key, a measure of each country’s capital contribution to the ECB that, in practice, reflects its population and contribution to euro-area GDP. Policymakers announced that the PEPP would not adhere rigidly to the capital key, a tacit signal that the program would try to support those countries most affected by Covid-19, such as Italy. A recent decision by the German constitutional court has thrown the program into doubt – the ruling threatens to prevent Germany’s national central bank, the Bundesbank, from participating in the ECB’s sovereign bond purchase program. The implications of this are, as yet, unclear.

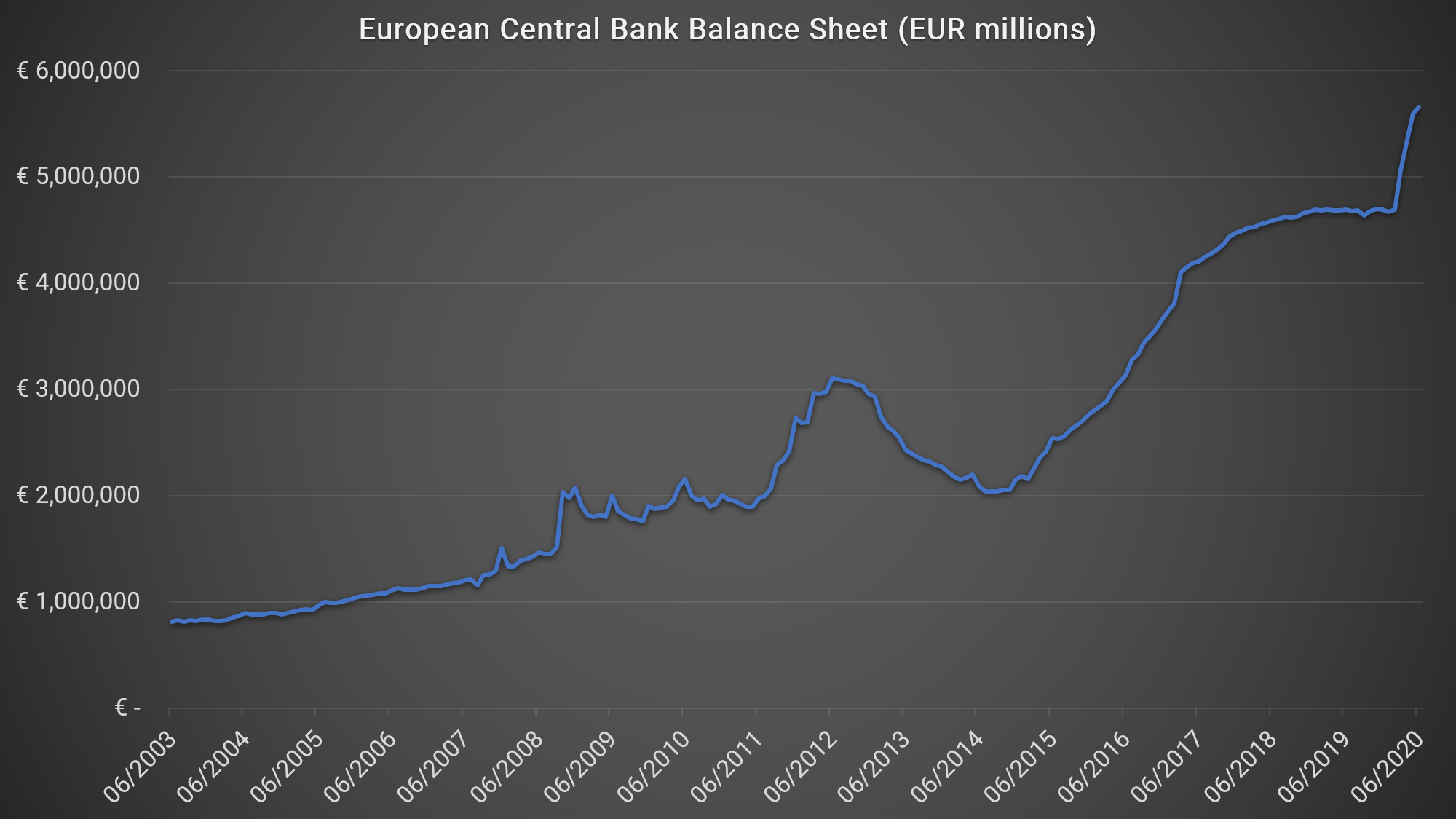

In addition to its interest rate and QE measures, the ECB, which supervises 115 major European banks that account for over 80% of eurozone banking assets, has eased capital rules for banks, encouraging them to use their liquidity buffers to lend. It has also relaxed certain rules around nonperforming loans and eased collateral restrictions to help banks maintain liquidity, and it is lending to banks through its long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), newly announced pandemic emergency long-term refinancing operations (PELTROs), and expanded targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). These combined QE activities have led to a rapid expansion in the ECB’s balance sheet assets.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. ECB Assets. June 2020.

The Bank of Japan response

The BOJ has spent decades battling a secular decline in the Japanese economy and persistent low inflation and deflation. Like the Fed and the ECB, the BOJ anticipates that the Japanese economy will be hit hard by the coronavirus.

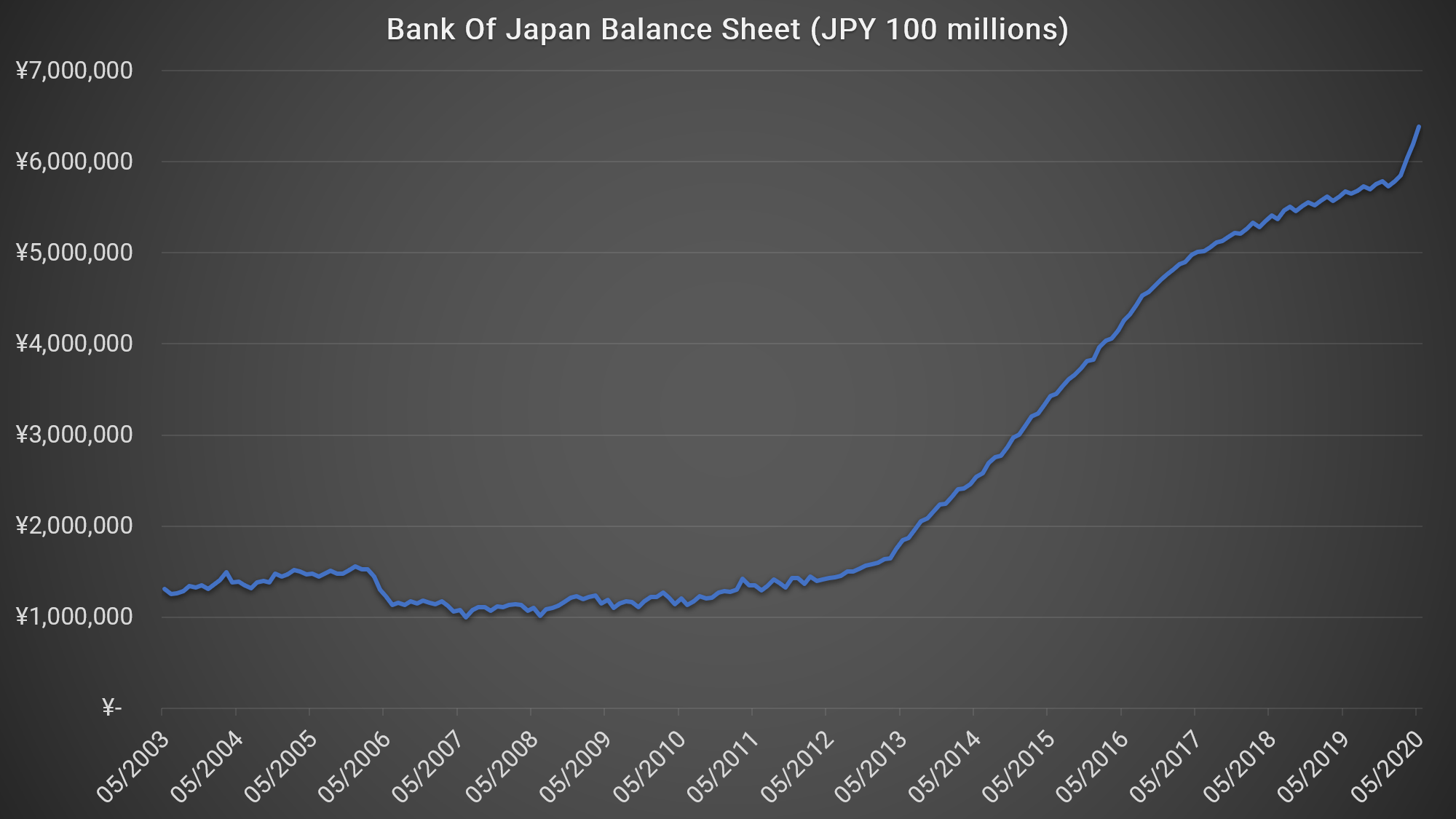

In response, it has expanded its QE program, removing the limits on the amount of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) it can purchase. After years of QE, the BOJ owns over 50% of outstanding JGBs and this is likely to grow further as it pursues a policy of unlimited QE. It has also maintained its negative interest rate policy and signaled that this policy will remain in place until growth and inflation resume.

Unusually, the BOJ is also active in Japanese equity markets through its equity ETF buying operations. The BOJ directly purchases ETFs that invest in Japanese equities – it accounts for an estimated 75% of the ETF markets and owns an estimated 10% of the total Japanese equity market. In response to the current crisis, the BOJ has doubled its net equity ETF purchases target.

The BOJ is also active in various Japanese debt markets, including corporate bond and commercial paper markets. It has expanded its various asset purchasing programs to provide additional funding to Japanese businesses. Over the years, these various QE activities have greatly expanded the BOJ’s balance sheet and the pace of accumulation is rising fast.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. BOJ Assets. June 2020.

Long-term implications

The extent of current central bank actions – which also include various interbank swap agreements aimed at ensuring that there are enough euro, yen, and most importantly, dollars available to sustain the international banking system – are without precedent and we have entered unchartered economic and monetary waters.

Despite central banks’ aggressive monetary policy stances, long-term interest rates remain subdued, in large part due to their “yield curve control” efforts – essentially, using bond-buying operations to influence interest rate levels across the yield curve, a form of debt price-fixing. This suggests that inflation will remain under control and economic growth will remain relatively tepid.

However, many economists warn that the rapid growth in the money supply will feed into long-term inflation and that the enormous debt piles built up during this crisis and the GFC will act as a drag on economic growth prospects. This combination could result in stagflation – a challenging economic situation in which high inflation is coupled with low growth in a vicious cycle.

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials that are relevant to global central banks and other topics discussed above. Click one of the links below to see the intro video for that tutorial.