Big Oil, Big Problems: Listed Oil Majors Are Under Fire, But Oil Production Is Rising

During just a few days in May, three of the world’s largest listed oil companies were dealt powerful public blows by climate activists. In the face of shareholder revolts and legal challenges, energy supermajors including Chevron, Exxon Mobil, and Royal Dutch Shell now appear to be bowing to the inevitable on climate change and preparing to embrace a low carbon future. Yet it’s too soon to claim victory for green activists – global oil production is on the rise as national oil champions move to pick up the slack left by the retreat of the supermajors. Is it a case of “Big Oil is dead, long live Big Oil” or is the shift to renewables finally taking hold?

During just a few days in May, three of the world’s largest listed oil companies were dealt powerful public blows by climate activists. In the face of shareholder revolts and legal challenges, energy supermajors including Chevron, Exxon Mobil, and Royal Dutch Shell now appear to be bowing to the inevitable on climate change and preparing to embrace a low carbon future. Yet it’s too soon to claim victory for green activists – global oil production is on the rise as national oil champions move to pick up the slack left by the retreat of the supermajors. Is it a case of “Big Oil is dead, long live Big Oil” or is the shift to renewables finally taking hold?

Boardroom drama

At Exxon, the climate reckoning came in the form of a contentious shareholder vote.

Shareholder dissatisfaction had been growing after several projects – including investments in Canadian oil sands – failed to pay off. Some shareholders were also critical of the company’s apparent reluctance to invest in green growth areas such as solar and hydrogen.

Against this backdrop, activist investors led by a small hedge fund named Engine No. 1 nominated four pro-environmental candidates to the Exxon board in a bid to shift the company’s strategic direction.

Exxon campaigned vigorously against these candidates, flooding shareholders with materials urging them to vote for its own nominees. Many observers doubted that Engine No. 1 could win in the face of Exxon’s resistance, especially as it is a minority shareholder with just a 0.02% stake. However, the hedge fund was able to gain the support of major Exxon shareholders such as BlackRock and Vanguard, which are vocal proponents of incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues in investment decisions.

With the backing of these big players, Engine No. 1 unexpectedly won seats for three of its four board candidates in what is widely seen as a major rebuke to Exxon management (the vote has yet to be certified and reported to the SEC, but Exxon has indicated that this is the final tally).

A similar drama played out at Chevron, where 61% of shareholders rebelled against the board to vote in favor of a proposal to force the company to cut its carbon emissions.

The proposal came from climate campaign group Follow This, which had already successfully pushed through similar resolutions at ConocoPhillips and others. The proposal targets so-called “Scope 3” emissions – GHG emissions caused by the burning of the company’s product by customers. Scope 3 emissions account for most of oil majors’ GHG emissions – over 90% in the case of Chevron.

Chevron’s board had instructed shareholders not to vote for the proposal, but investors defied management to register their unhappiness with the slow pace of change at the energy giant.

Courtroom drama

Meanwhile, in Europe, Royal Dutch Shell faced a different type of reckoning in the courtroom. In a case brought by climate campaigners, a Dutch court ruled that Shell’s existing climate strategy was insufficient and that the company had a human rights obligation to cut its net carbon emissions 45% by 2030 compared to its 2019 levels.

The ruling applies immediately, with no delay for appeal. Therefore, Shell CEO Ben van Beurden has said that the company will fast track plans to slash emissions in what plaintiffs hailed as a significant victory for the environment.

Broader transformation

While these events have grabbed headlines, campaigners can also point to other indicators that the climate message is finally being heard in the boardrooms of the world’s energy businesses.

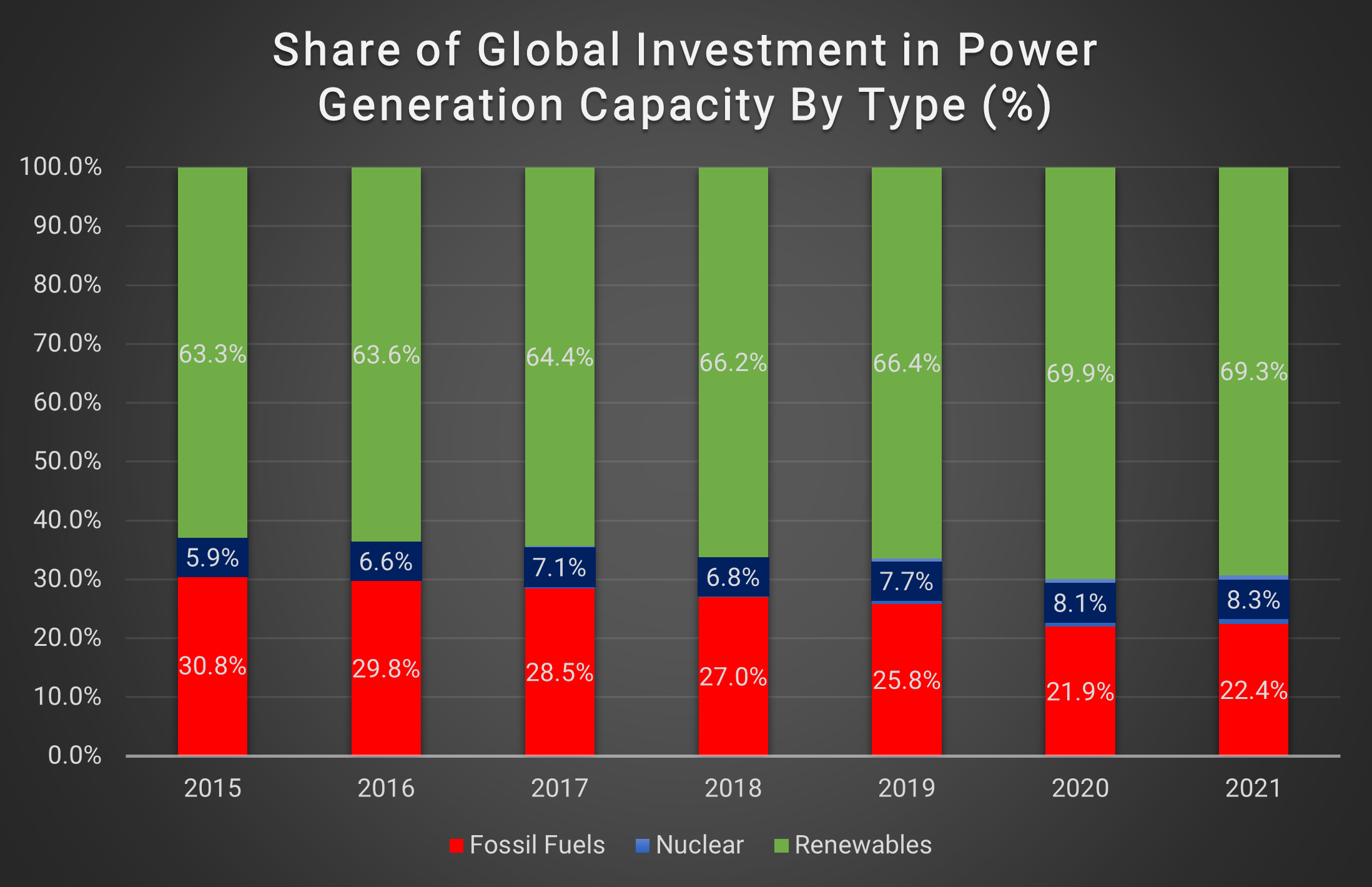

Data from the IEA, for example, shows that investment in renewable power generation capacity – including bioenergy, hydropower, wind, geothermal, solar, and marine energy – dominates global spending (see chart) on generation capacity.

IEA. International Energy Agency World Energy Investment 2021. June 2021. 2021 figures are an estimate.

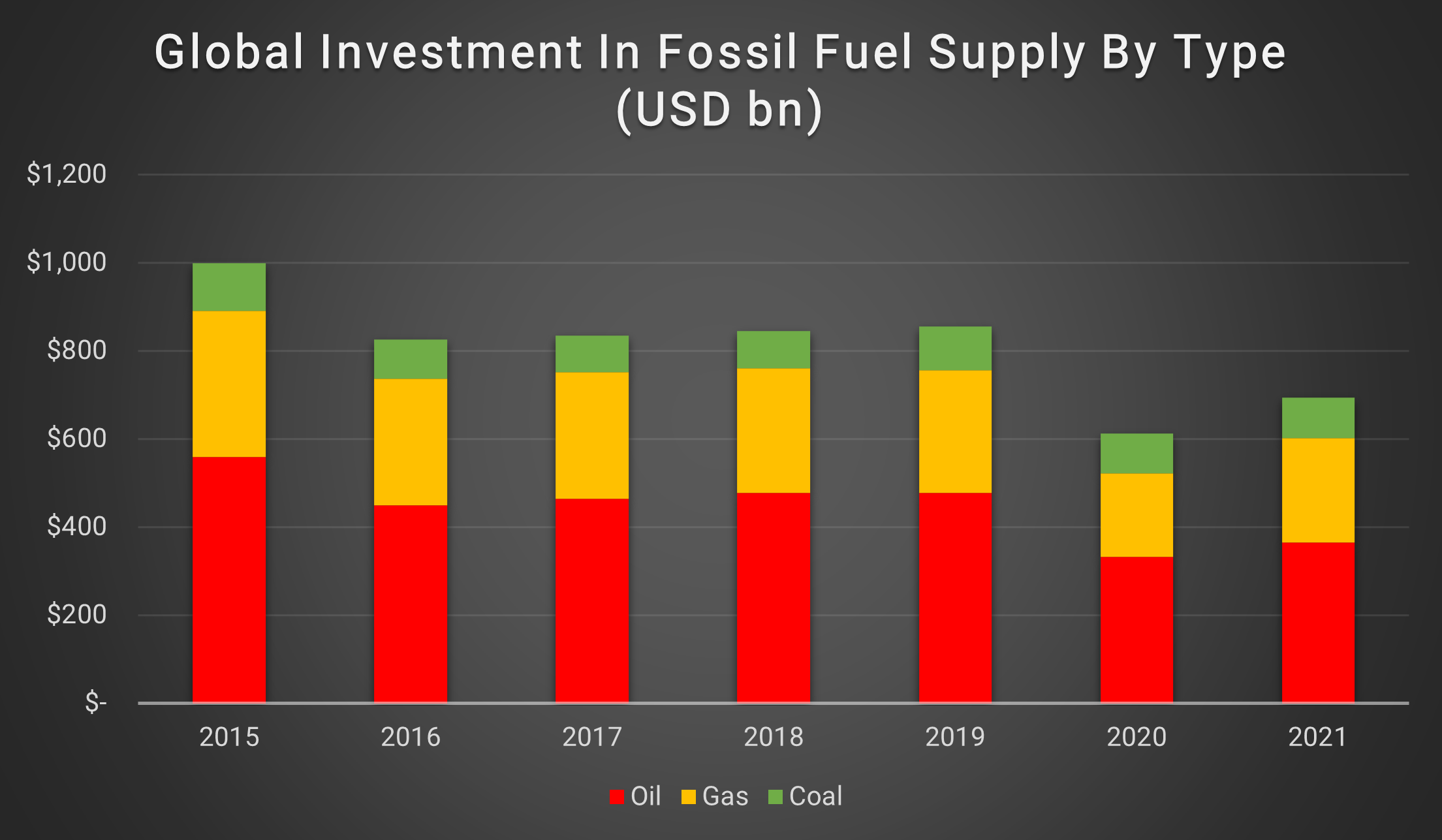

At the same time, spending on fossil fuel supply – which includes upstream activities such as prospecting, as well as midstream infrastructure such as pipelines, and activities such as refining – has been falling over the last few years (see chart).

This suggests a lack of appetite for investing in new fossil fuel sources and power generation capacity, which may indicate that the industry is in the process of transitioning away from carbon-intensive energy – although it is important to note that fossil fuels continue to dominate existing infrastructure.

IEA. International Energy Agency World Energy Investment 2021. June 2021. 2021 figures are an estimate.

All of this is encouraging news for those concerned about fossil fuels’ impact on the climate. However, there is reason to suspect that the situation is not as clear-cut as it seems.

Fossil fuel dominance

Demand for fossil fuels remains robust despite decades of climate activism. After falling during the pandemic, oil demand is roaring back and – according to oil cartel OPEC – is expected to hit 96% of its 2019 level this year. Similarly, demand for natural gas has risen steadily over the last few years and is resurgent this year after a slower 2020.

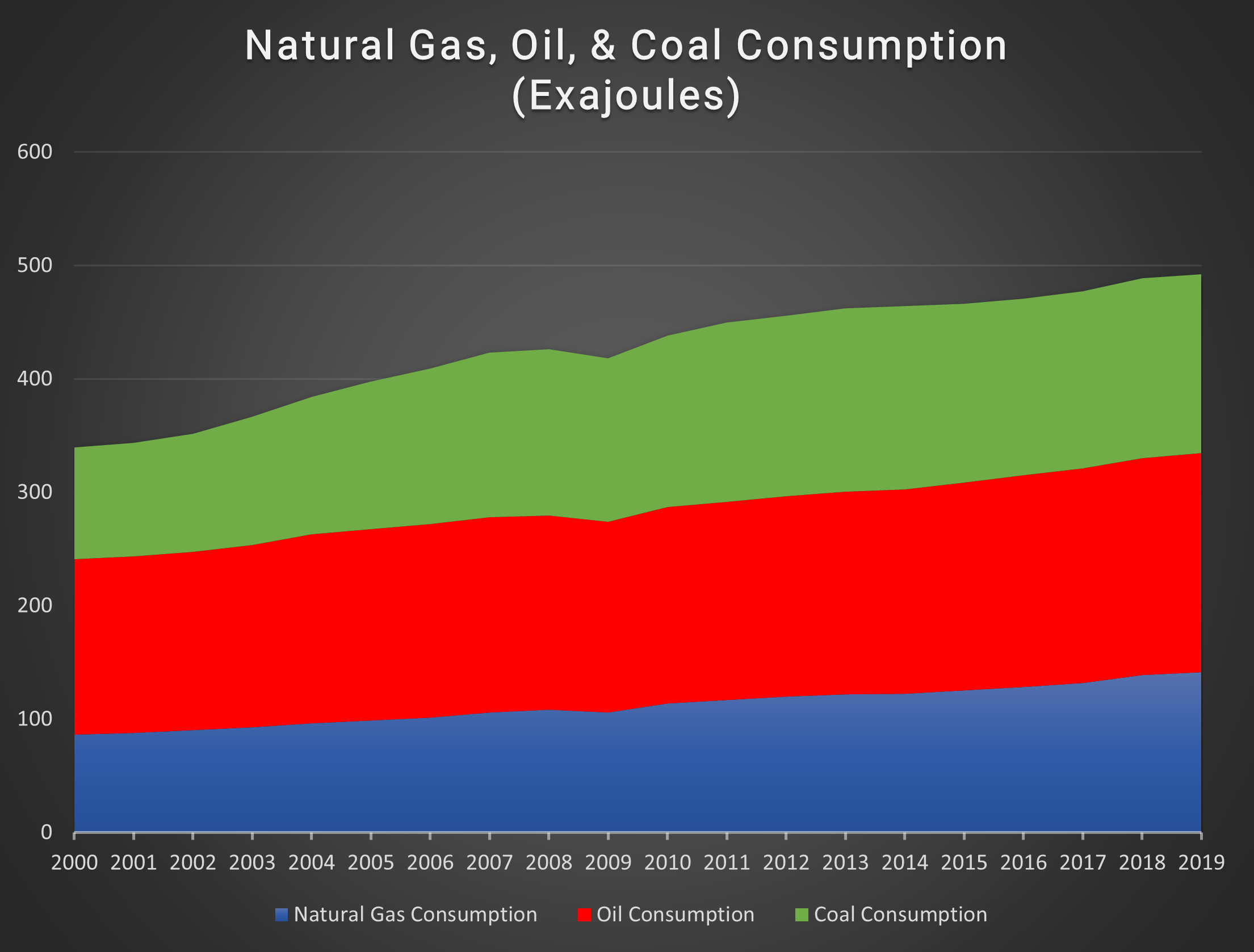

Overall, global consumption of fossil fuels as measured in units of energy consumed rose 45% between 2000 and 2019, according to BP’s latest Statistical Review of World Energy (see chart).

In other words, while a growing number of voices are calling for a low carbon future, human activity is driving ever-rising fossil fuel consumption.

B.P. Statistical Review of World Energy 2020. June 2020.

The rise of NOCs

How do we square this circle of falling investment in fossil fuels with rising demand and consumption?

Part of the explanation is that, even though new investment in fossil fuel supplies and power generation is falling, prior decades of strong investment mean that there are plenty of reserves on oil companies’ balance sheets and plenty of fossil fuel power plants that require maintenance spending only.

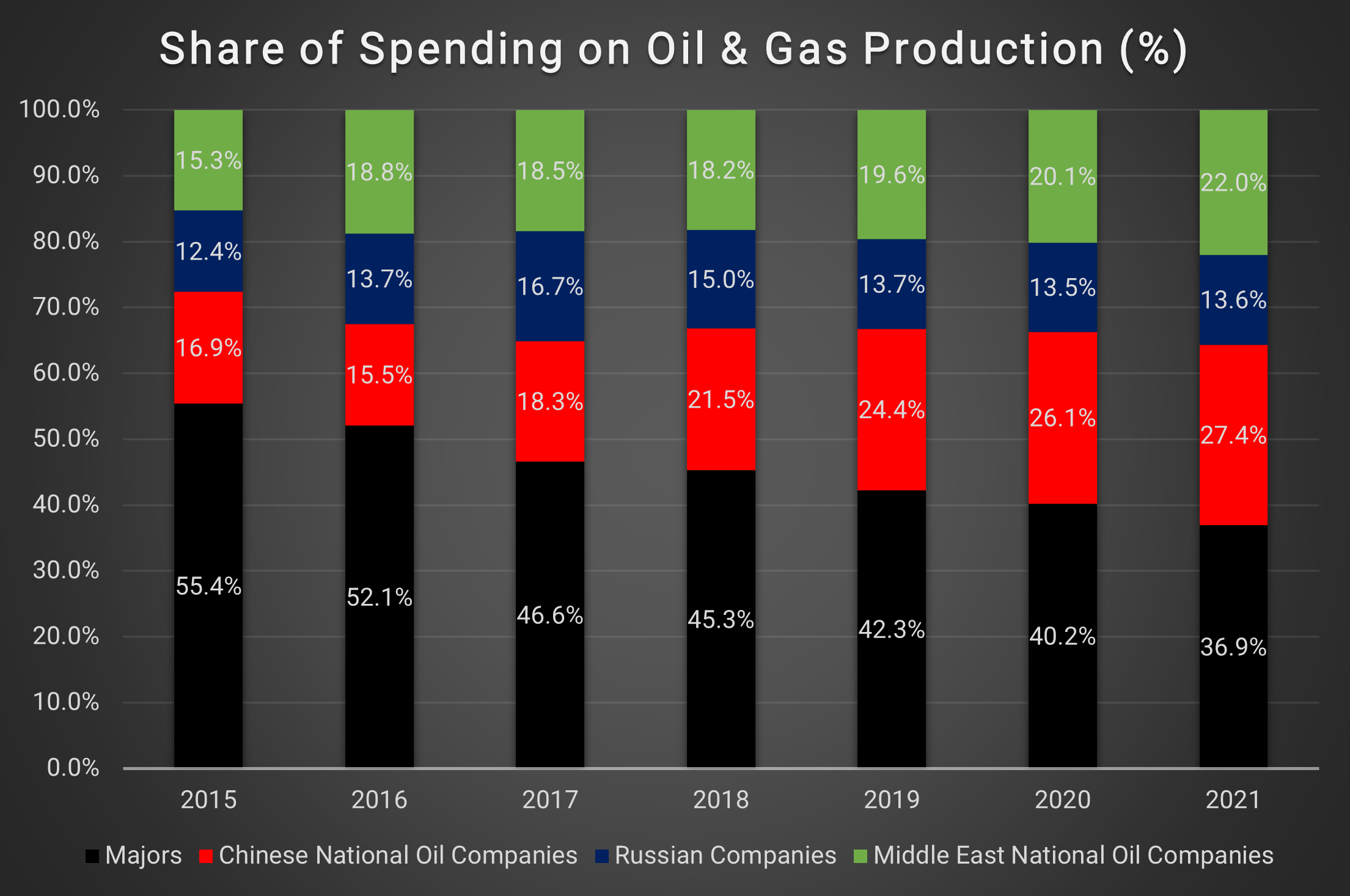

Another part of the explanation has to do with national oil companies (NOCs). While listed entities such as Exxon and Shell must worry about activist shareholders and dissident board members, state-owned oil companies such as Qatar Petroleum, Saudi Aramco (which is partially listed), and Abu Dhabi National Oil Co., are largely insulated from such pressures. As the listed oil majors have cut their investment spending in the oil & gas sector, Middle Eastern and Chinese NOCs have increased theirs (see chart). This suggests that in the future NOCs, which currently produce about 50% of the world’s oil, will account for a rising share of global production.

IEA. International Energy Agency World Energy Investment 2021. June 2021. 2021 figures are an estimate.

The growing role of NOCs in world energy markets suggests that a climate strategy that exclusively targets listed oil majors is insufficient. As long as demand for oil and other fossil fuels remains high, businesses will meet that demand. Climate campaigners must, therefore, look beyond listed oil majors if they want to reduce our dependence on carbon-emitting fuels.

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials that are relevant to ESG issues and the oil industry:

- ESG & SRI – Primer

- ESG & SRI – An Introduction

- ESG & SRI – Investing

- ESG Factors

- Green Assets

- Commodities – An Introduction

- Commodities – Trading

- Commodities – Oil

- Commodities – Natural Gas

- Commodities – Emissions