Coronavirus Set To Crush Emerging Markets In Worst-Ever Crisis

As some European and North American coronavirus hotspots start to see light at the end of the tunnel, many emerging markets are bracing for the worst of the impact. More and more developing countries are imposing lockdowns to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, even as the global “coronacrisis” is set to devastate their domestic economies and dislocated financial markets threaten their access to capital. As emerging markets grapple with this three-fold challenge, some are warning that they may face their worst-ever emergency.

There are encouraging signs of improvement in some of the wealthy countries that are home to coronavirus hotspots, such as Italy and the United States. In many of these nations, leaders are starting to plot a course out of lockdown, considering how best to slowly restart their stalled economies.

However, even as green shoots spring up in rich nations, emerging markets are facing devastation. Countries such as India, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, and many others have seen growing domestic outbreaks of coronavirus. At the same time, as wealthy countries have shut down, emerging markets have seen exports collapse along with travel and tourism revenue. Compounding the pain, oil prices have slumped – dealing serious damage to oil-dependent emerging markets such as Nigeria – and financial markets have partially seized up amidst an investment flight to safety.

It’s a perfect economic storm, made worse because today’s heavily indebted emerging markets are even more vulnerable than they were before the 2008 financial crisis. As a group, they may be facing their worst-ever catastrophe.

Coronavirus outbreaks and lockdowns

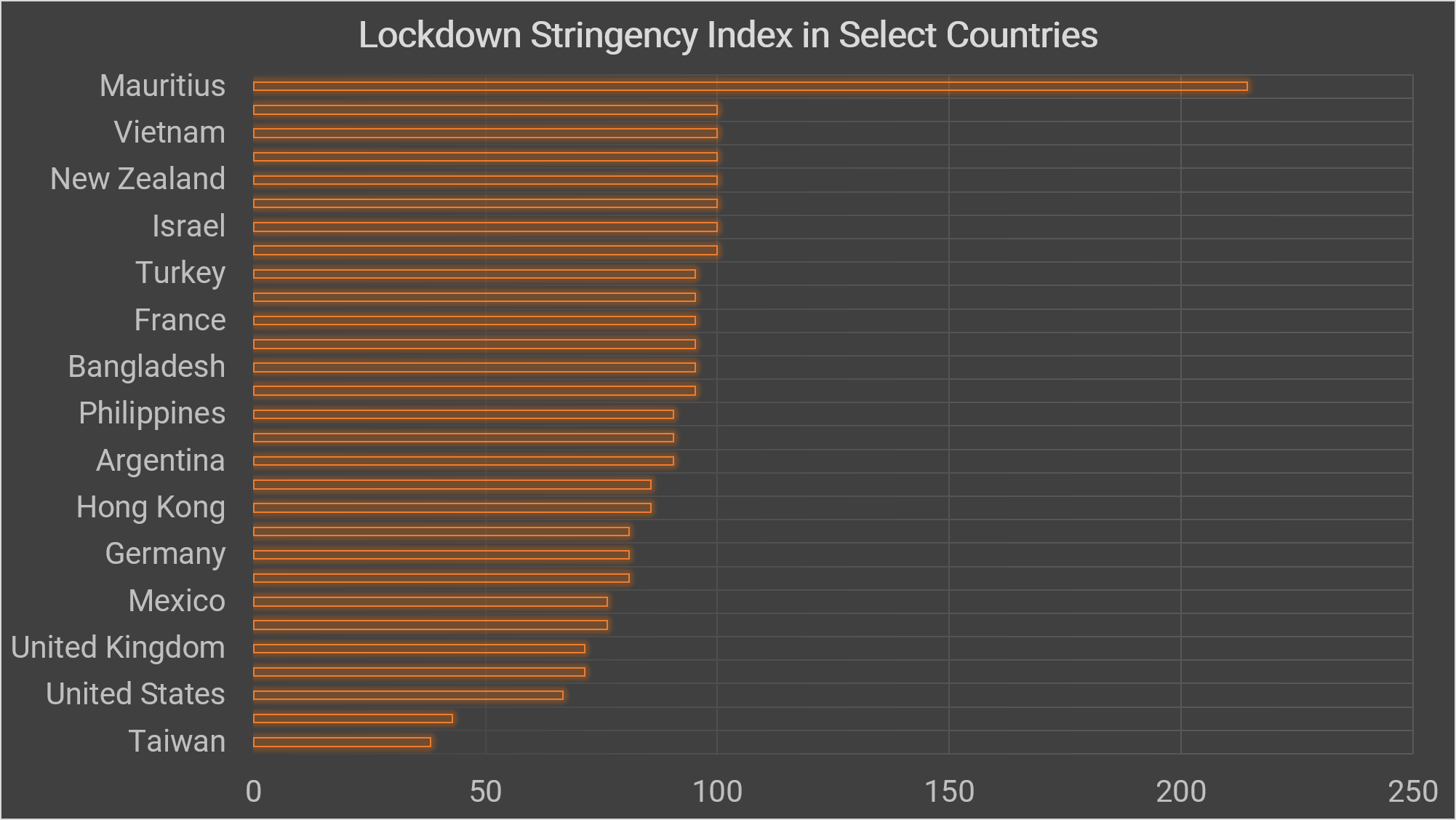

Around 30 emerging economies have imposed lockdowns in the face of coronavirus outbreaks, including India, Pakistan, Vietnam, South Africa, Malaysia, and Mexico. Measures range from travel bans to total economic closure – according to data compiled by Oxford University, countries like Mauritius, India, South Africa, and Mali have some of the world’s harshest restrictions.

Hale, Thomas, Sam Webster, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, and Beatriz Kira (2020). Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker. April 2020.

Governments hope that these restrictions will slow the spread of the deadly coronavirus, sparing their fragile health systems and saving lives. However, they are coming at a steep economic cost at a time when emerging markets are already struggling.

Economic devastation

The first country to implement a coronavirus lockdown was China, where the virus first emerged. That initial lockdown had several knock-on effects on China’s trading partners and on emerging markets more generally. Reduced demand from China threatened commodity prices and funds began to flow out of emerging markets.

As the coronavirus spread to wealthy nations, the economic pain intensified. Travel bans multiplied, consumer demand collapsed, and many countries across Europe and North America imposed restrictions on economic and social activity in a bid to slow the spread of the virus. These lockdowns led to a near-total collapse in global demand for travel, tourism, luxury goods, clothing, and many other products and services – including oil. Emerging markets’ exports plunged, starving them of much-needed foreign currency and sharply contracting their economic activity. Further, as these countries imposed their own lockdowns, domestic demand collapsed, worsening the pain.

Financial market dislocation

The next phase of the crisis came as financial markets began to seize up. Stock markets plunged and worrying signs emerged in major credit markets – even the market for US Treasuries, usually the world’s most stable instruments, showed signs of dislocation. Major central banks acted quickly to contain the fallout. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB) rolled out a host of emergency monetary policy measures. The Fed flooded markets with liquidity and the ECB moved to shore up European bond markets.

While these actions helped to stabilize global financial markets, they – together with rising risk aversion among investors – imposed a fresh wave of pain on emerging markets.

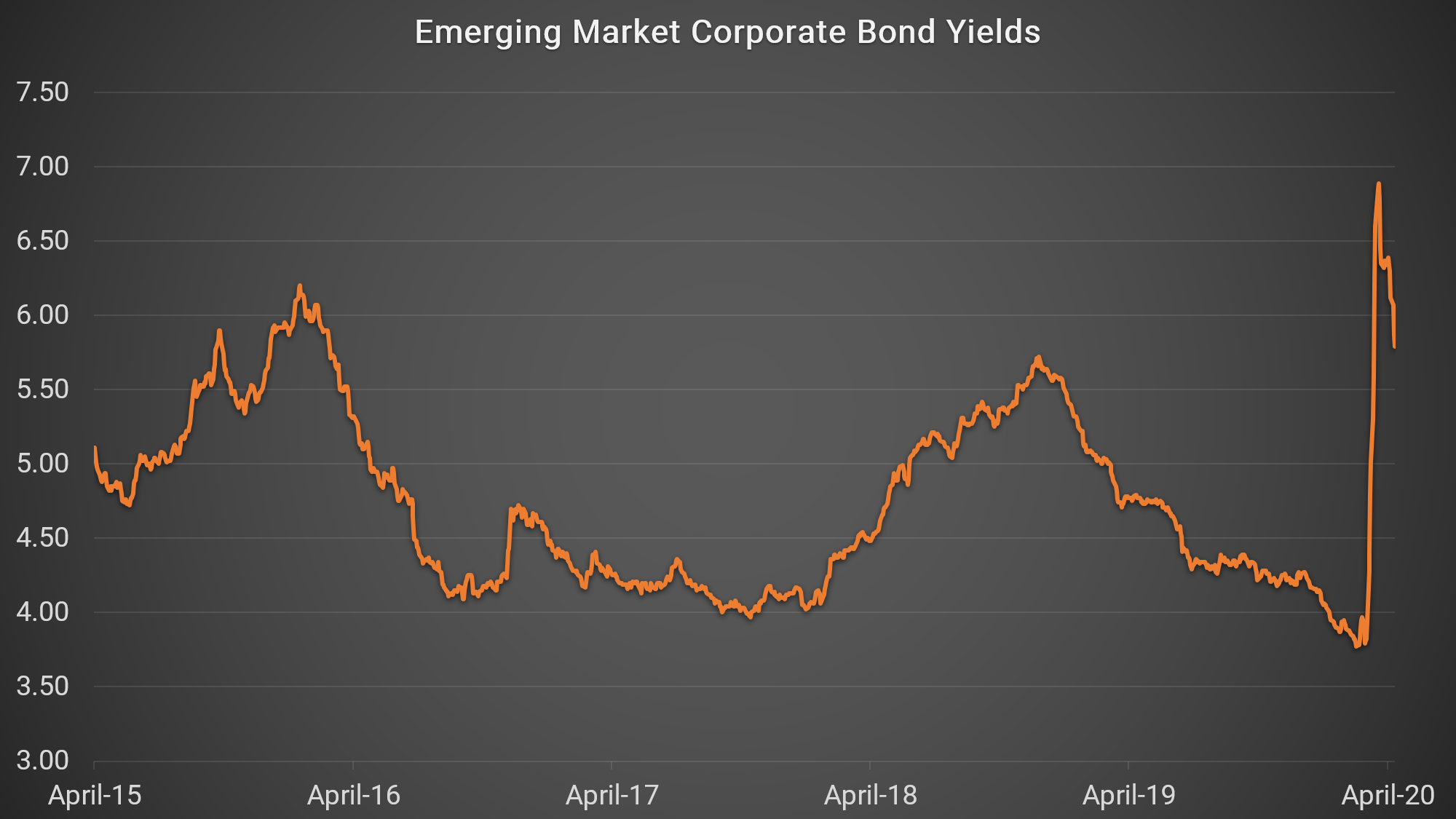

According to the Institute of International Finance, a record $83 billion flowed out of emerging market shares and bonds in March as investors fled to the safety of US Treasuries and other dollar- and euro-denominated assets. These outflows sent emerging market stock markets crashing and led to spikes in bond yields.

Ice Data Indices, LLC, ICE BofA Emerging Markets Corporate Plus Index Effective Yield, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Both corporate and sovereign emerging market were sold aggressively, and the major credit rating agencies issued several sovereign debt downgrades for these markets. This withdrawal of liquidity threatens to create a fresh financial crisis. While the situation has stabilized somewhat, the risks remain high.

Emerging market borrowing has grown steeply since 2009, buoyed by ultra-low interest rates in the US and Europe that drove yield-seeking investors to pile into emerging market debt instruments, which were often denominated in dollars. According to Foreign Policy, a US news magazine, internationally traded emerging market corporate debt quintupled to $2.3 trillion between 2007 and 2019.

Today, faced with tighter borrowing conditions, plunging exports, and frozen domestic economies, many of these corporate borrowers are now facing rising default risk. Worse still, there is a global shortage of US dollars due to peaking demand. The Fed has reopened its financial crisis-era liquidity swap lines, providing dollars to desperate foreign central banks, but among emerging markets, only Brazil and Mexico have access to the facility.

For others, the dollar drought, together with investment outflows, are combining to send many emerging market currencies into freefall, making it even more difficult for borrowers in these markets to repay their hard-currency debts. As emerging market governments eye debt freezes and relief, market conditions remain tense.

Government responses

The final factor exacerbating the crisis in emerging markets is their governments’ limited capacity to respond. While wealthy countries have been rolling out unprecedented fiscal policy responses to the economic pain associated with coronavirus, emerging markets have been unable to do the same. Many, including key countries like Brazil and Mexico, lack automatic stabilizers like unemployment insurance, which are helping ease the pain in wealthy nations.

In addition, because they are facing rising borrowing costs and collapsing currencies, many emerging markets are struggling to raise debt to finance an emergency fiscal response. Thus, the economic impact of the coronavirus will be felt far more deeply by emerging market households and businesses than their wealthy country peers.

Strong action by global institutions and wealthy nations is needed to avert an emerging market crisis, which could spread even more economic pain around the world. Unfortunately, an increasingly isolationist US seems uninterested in leading a global effort to help troubled nations, while Europe is grappling with its own economic woes and most multilateral global institutions are constrained by budget cuts and declining US support. Unless things change, the outlook for emerging markets and the global economy looks grim.

Intuition Know-How has a number of tutorials that are relevant to emerging markets and other topics discussed above:

- Emerging Markets – An Introduction

- Emerging Markets – Advanced & Secondary Markets

- Emerging Markets – Frontier Markets

- Bond Markets – An Introduction

- Fixed Income Analysis – Credit Risk

- Monetary Policy Analysis

- Fiscal Policy Analysis